Hedy Strnad

Paul and I loved living in Prague. We had a good life there. The city was alive with culture, history, and the arts.

Although I was born in Prague, we still spoke German at home because my family had emigrated from more rural Bohemia before I was born. Of course, we also spoke Czech and even learned English. When I lived there in the early 20th century, Prague was home to 35,000 Jews and the community was flourishing: Jews were in local government, there were several Jewish social, relief, and educational associations. Jews also enjoyed success in the arts-theater, music, fine art and literature. If you visit my home town today, you’ll see we still adore Franz Kafka, a German-speaking Jew like myself.

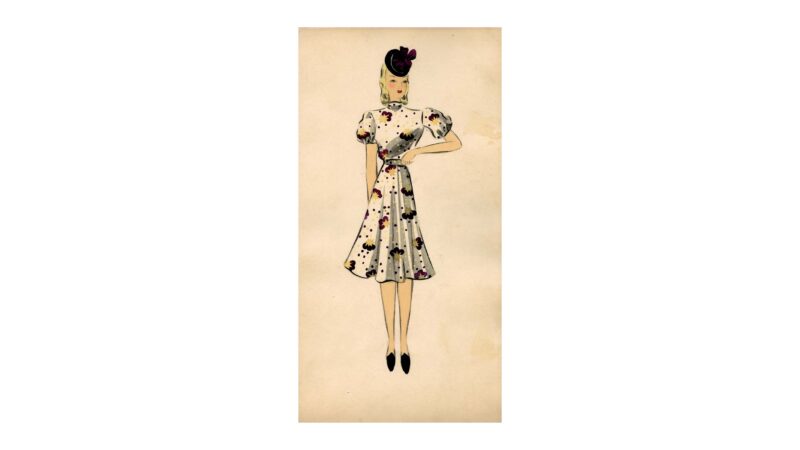

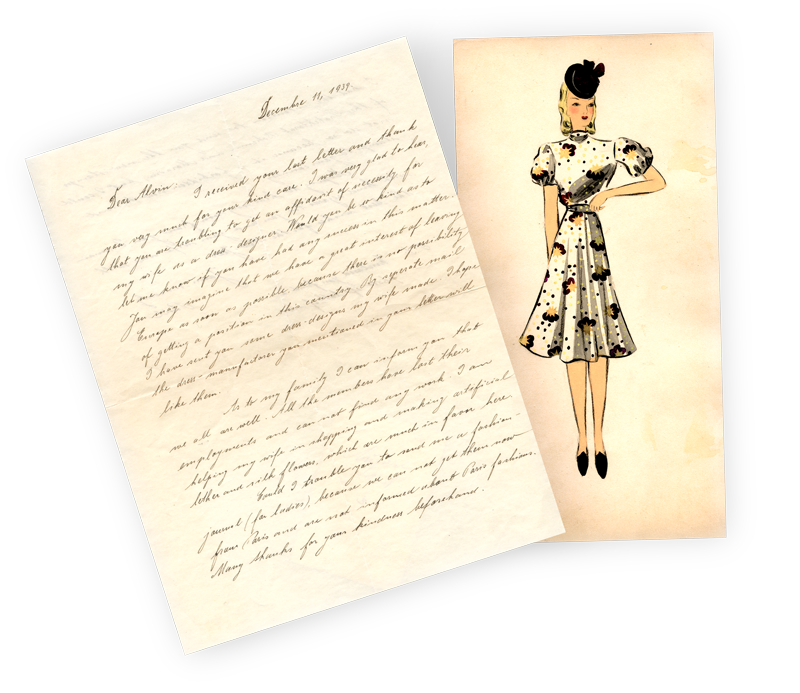

I enjoyed making a living as a women’s clothing designer and shopkeeper in ‘The City of Lights’. Many Jews were in the textile business like me. My seamstresses and I did fine work; I read fashion magazines from Paris and we created beautiful, chic women’s outfits. From tailored suits to flowing gowns, I enjoyed outfitting women in the fashions of our time. Paul and I were content. With no children and two incomes we lived a very comfortable life and enjoyed our free time with friends and family.

Alarm bells started to ring when fascism took hold in Germany, but they sounded distant and distinct from what we were experiencing in Prague and our concern didn’t spur us to leave. We convinced ourselves with the logic of history: Jews had lived in Czech lands for centuries, religious intermarriage was quite common, and tolerance was one of the primary features of our beautiful city.

By the late 1930’s however, the bells were tolling much louder. As the Nuremberg Laws made life in Germany nearly impossible for Jews, the number of Jewish immigrants to Prague ballooned. Suddenly there were 56,000. As we know from history, any time there is a sudden surge in the population, it pinches the local economy and infrastructure which can generate antagonisms to the people coming in. When those people are Jewish, the Western world has a tendency to default to thousands of years of Anti-Jewish sentiment. There was a terrible irony at play: Jews were fleeing antisemitism in Germany, but their arrival in Czechoslovakia kick-started an era of radical antisemitism in this place of refuge. In what seemed like a blink, the Czech way of life had shifted. My husband and I had never witnessed the sort of intolerances that we started to see on a daily basis.

On September 30, 1938, the Nazi influence on Czechoslovakia became all the more profound with the signing of the Munich Agreement, which allowed the annexation of the Sudetenland, a portion of Czechoslovakia where my family had come from and where my father and sister-in-law still lived. With nowhere to go and with their homes confiscated they moved East to be with me and Paul in Prague. We were of course not alone in housing exiles from the Sudetenland.

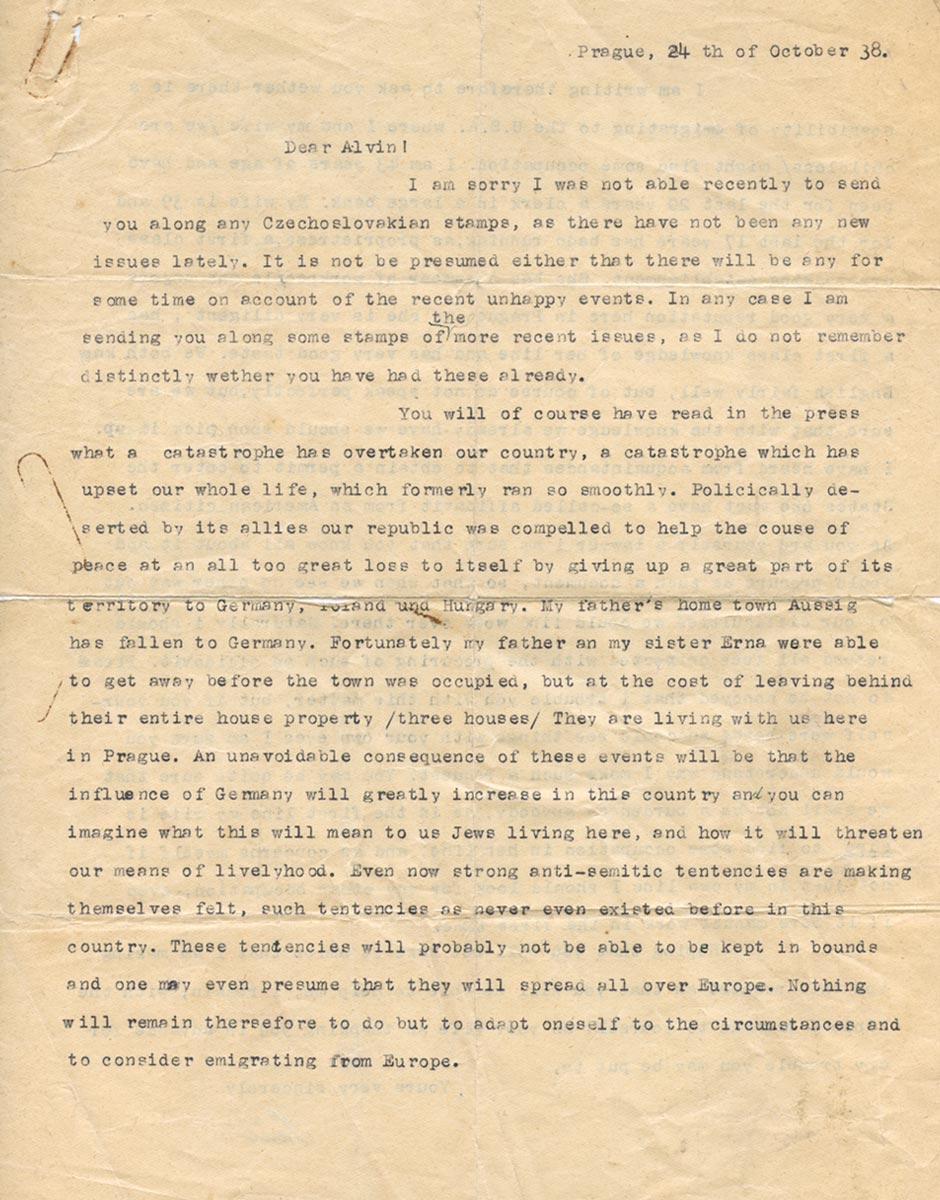

Given the Nazi rhetoric and the antisemitism that was growing throughout Europe, Paul and I started to feel anxious about leaving. We began to make plans to emigrate to the United States. As Paul predicted, it would be only a matter of time before broader anti-Jewish policies and practices spread across Europe. Paul had a cousin in Milwaukee named Alvin Strnad who he was in regular contact with. In October 1938, Paul wrote to Alvin to see if he could provide what was called an “affidavit of necessity” so we could get a visa to come to the U.S. We knew the endorsement of an American citizen would help us overcome a few seemingly impenetrable barriers. First, we knew that America had reduced the number of Jews who could immigrate in 1924 with the Johnson-Reed Act. This created a quota system that completely cut off immigration from Asia and slowed the rate of emigres from Europe to a trickle. Even in the midst of war, the U.S. decided alongside many other nations at the Evian Conference, not to increase their Jewish immigration quotas. And we had a sense that popular opinion in America was against accepting new immigrants. But we thought that, surely, the plight of Jews in the face of Nazism would soften some hearts and minds.

It was only a month later that the Kristallnacht happened. The news coming out of Germany was horrifying, and we saw local versions of the same thing in small and large towns all around us. Every day it seemed the stakes were getting higher and we hoped that the rest of the world might start to see how perilous our lives were becoming under the thumb of Hitler. For us, hopes were pinned on Paul’s cousin. We thought that he could vouch for us. Paul and I both spoke English and we had transferrable skills that would allow us to work and not burden the citizen taxpayers of the U.S. It was a sound argument in our minds. And we were flexible to doing whatever it took. Paul told Alvin he would be willing to take on manual labor if need be. Anything to get us out.

We were so relieved when Alvin wrote back and said he would help us, especially since by then there were German troops in Czechoslovakia. We set to work making plans and gathering needed documents. Paul and I were so comforted when our dear nieces, Liselotte and Brigitte departed for England as part of the Kindertransport program. At least the youngsters would be safe! Perhaps there would be a way to safety for us all.

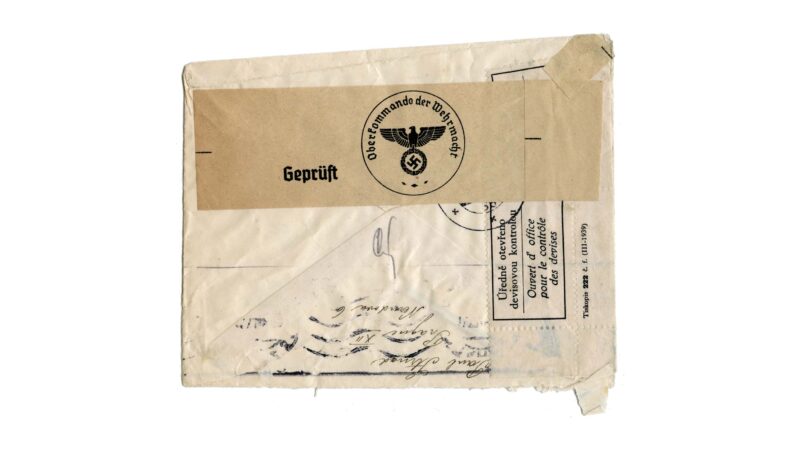

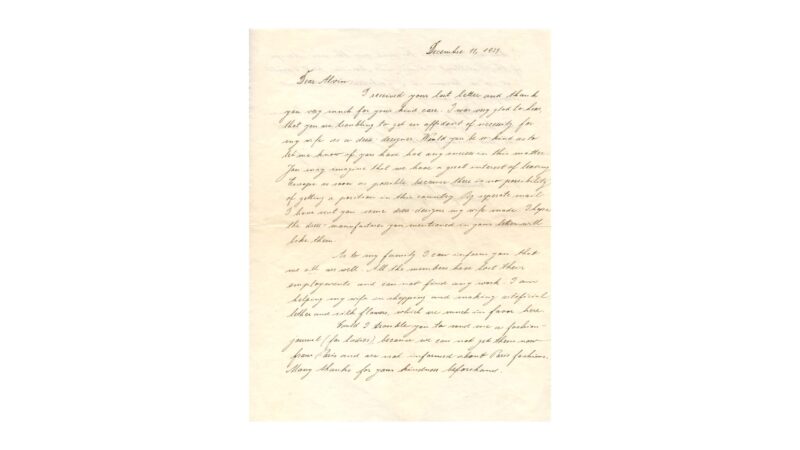

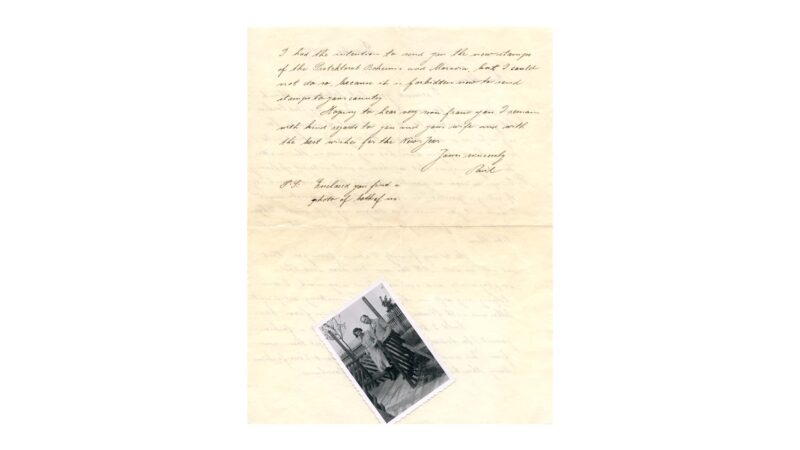

The situation became more worrisome and treacherous month after month. All our family lost their jobs and were unable to get work. In December of 1939, my husband again wrote to his cousin in Milwaukee. By then the Nazis were censoring letters so we had to be delicate with what we said. He did not overtly state the level of dread and fear we were living with, nor the true conditions of life that we were suffering; but he tried to make things apparent through some euphemisms and he was sure to confirm any fearful suspicions that were being aroused in the minds of Americans at that point. Whether it got the point across or not, we’ll never know.

We were able to send under separate cover eight of my designs that Alvin was going to show a dress manufacturer. We believed this might help us prove we would be productive citizens and that my talents, in particular, were valuable. My designs were heavily influenced by Western fashion and we both thought they would seamlessly transfer to the trends that were popular in the U.S. It was thought that artists and designers might be more thoughtfully considered for asylum because of their unique capacities. We heard of efforts to get famous artists out of Europe, and even though I wasn’t famous it was worth a shot.

We waited and waited. Nothing seemed to be moving except the German front. And when the U.S. entered the war in 1941 all visa application processing came to a near standstill. Our hope for escape was starting to fade during the summer of that year. In September, it was required that every Jew in Prague wear the Star of David on our clothes. And by November we saw friends being deported to concentration and forced labor camps.

Then on February 12, 1942, our greatest fears were realized. Paul and I were rounded up and transported via rail to Terezin, just outside of Prague, which the Nazis had converted into Theresienstadt Concentration Camp. There we joined thousands of others, many of whom were artists and intellectuals. The camp was horrendous, but the vitality of the people there was surprising and uplifting. Little acts of resistance were popping up all around us and glimpses of a glorious humanity that seemed like a distant past would occasionally emerge in full view.

But by April, Paul and I were again transported, this time to the Warsaw Ghetto in Poland. The ghetto was severely overcrowded and so when one person got sick, it spread quickly through the whole ghetto. People were starving and dying on the street. Nazi control over the region had suffocated any capacity to hear news of the outside world. Yet again, miraculously, the human spirit rose up against this persecution. There were underground libraries, an archive, and even a symphony orchestra. These acts of cultural resistance offered hope and allowed us to retain some sense of purpose, some belief in life itself.

My stay there was also not long. I was transported again, along with so many others, on a horrendous train ride to Treblinka. The Nazis had decided that simply collecting, starving, and torturing us was not enough. Their final solution was that we should all disappear.