Harry Soref

My friend Harry was a magician–probably the most famous one in the world.

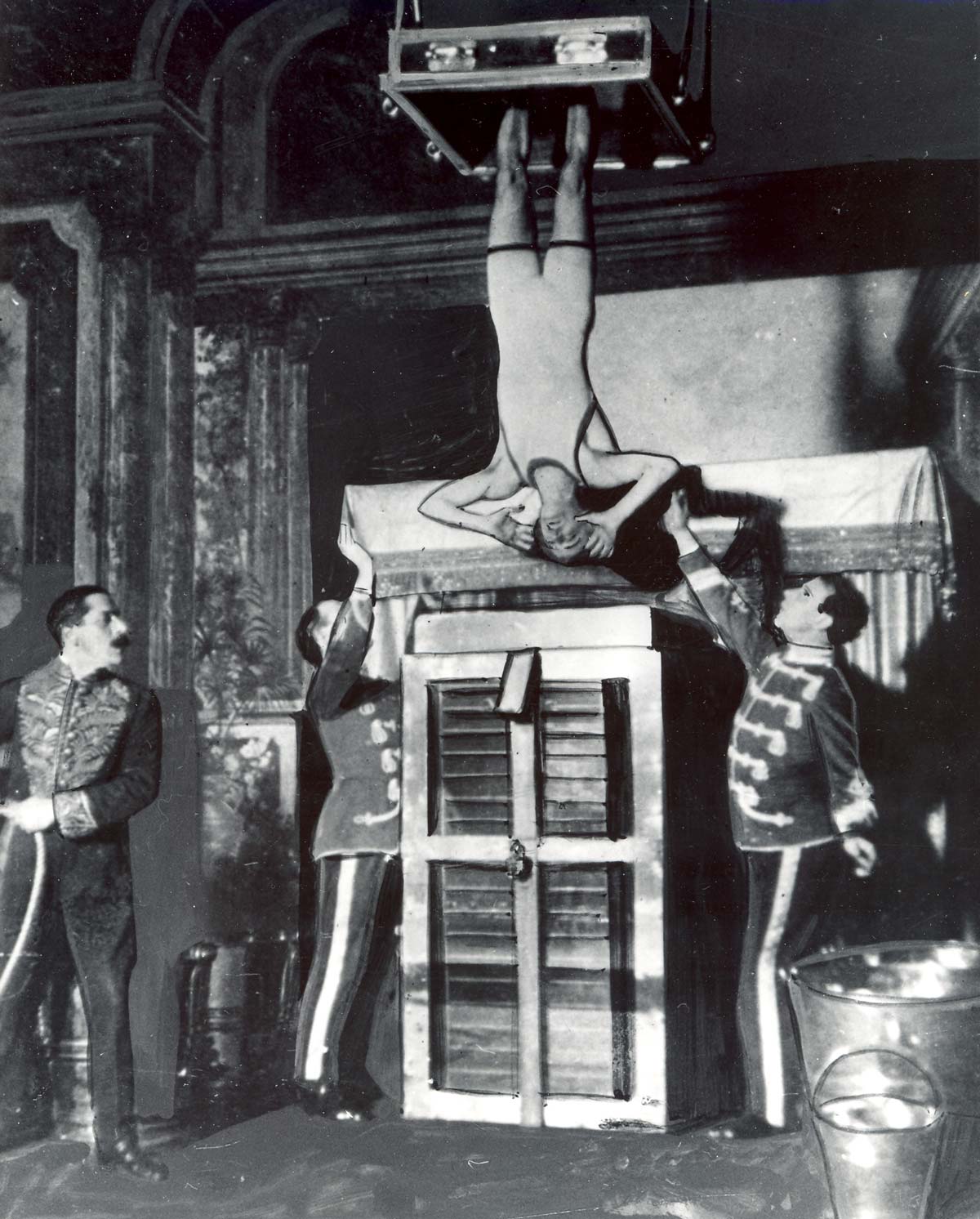

He started really making a name for himself after he moved to Milwaukee from Appleton and began doing all of these death-defying tricks. He was an expert at picking locks and so he’d get wrapped up in chains and handcuffs and all sorts of contraptions and find a way to wriggle out, sometimes while suspended upside down in a tank of water. People were completely transfixed by his bravery and skill.

Some thought that I had a hand in his shows. I guess it made sense: they knew that I had started out working odd jobs in the circus, which is where Houdini and I met, and I was known from my earliest days as a traveling locksmith. People thought I taught him where to hide keys or that I maybe made him some locks that could easily come apart when his life depended on it. I can see why the rumor was so catchy. But I’ll never reveal his secrets.

While I am not a magician like Harry, I certainly think that invention and innovation are a kind of magic, and I love to do both of those things. Tinkering with the world in a way that makes it better for everyone has always given me a sense of purpose.

One of the first things I created was a mechanism to fill holes in car tires. I discovered that by poking some rubber bands with glue into the puncture spot, the tire would hold air once again. The basics of ‘tire plugging’ are still the same today, but before I created this little tool, no one had thought to do it. No one will remember it this way, I’m sure, because my employer decided to patent the idea under their own name, rather than mine.

It irked me that someone would take my idea like that, but these sorts of things came pretty easily to me and I was already on to the next idea: master keys. I thought it would be good for people to have a set of keys that could open almost anything, in case they lost their originals. It seemed like a great idea to me and people liked having an opportunity to get themselves out of a jam. The police, on the other hand, didn’t like what I was up to: they said I was a thief’s best friend.

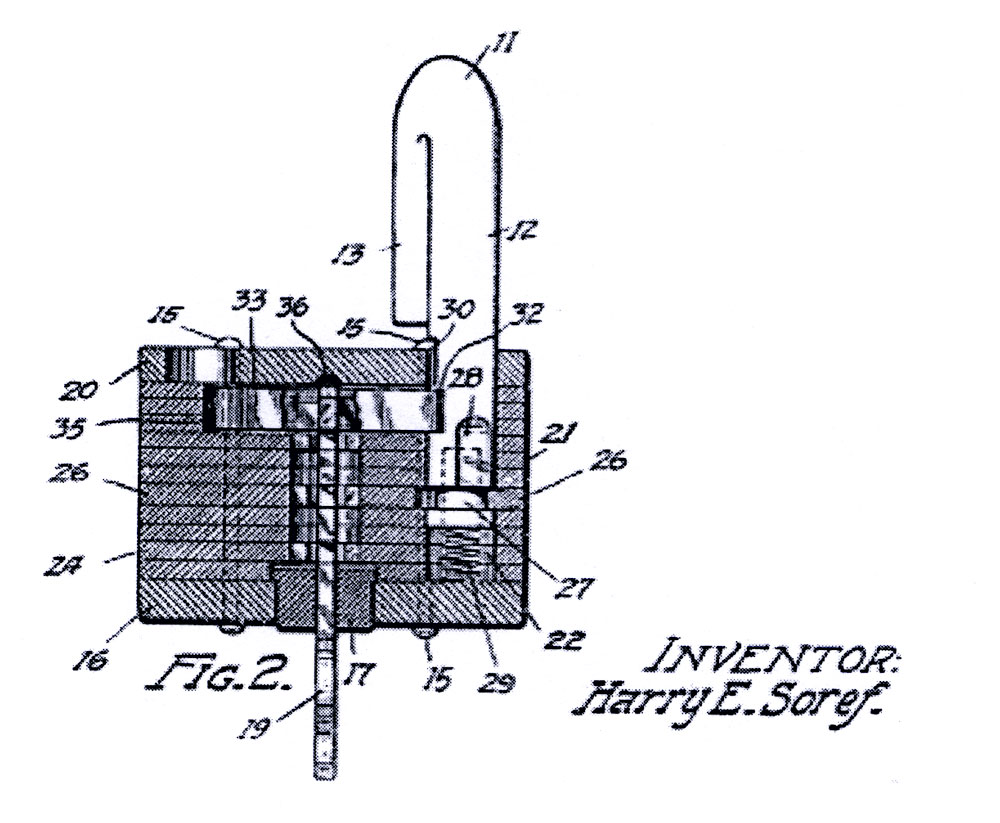

In my view, it wasn’t my fault that no one had made a good enough lock to fluster a simple five key system. But it gave me a thought: if locks were so easy to break, maybe I should try my hand at making one that couldn’t be beat.

So, I did.

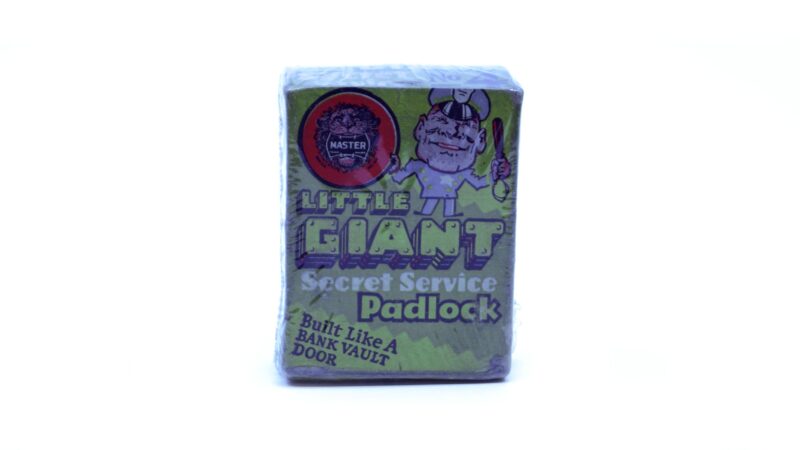

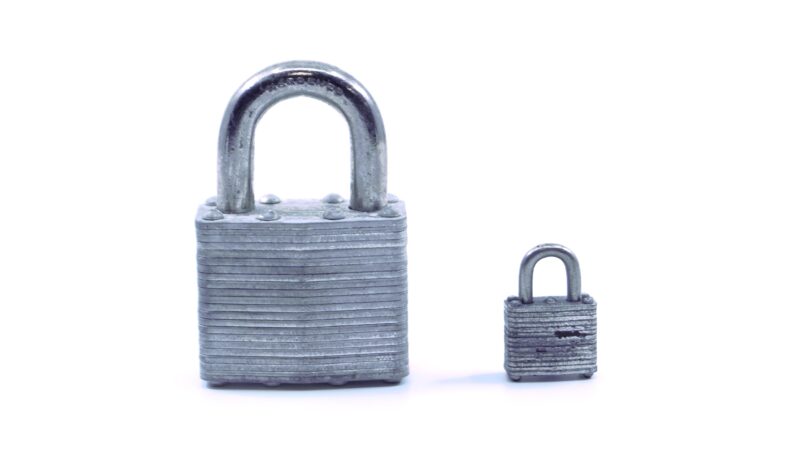

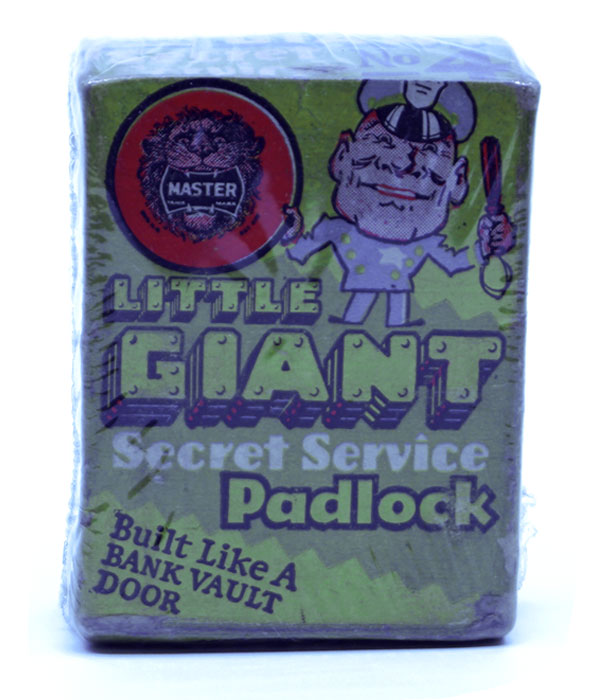

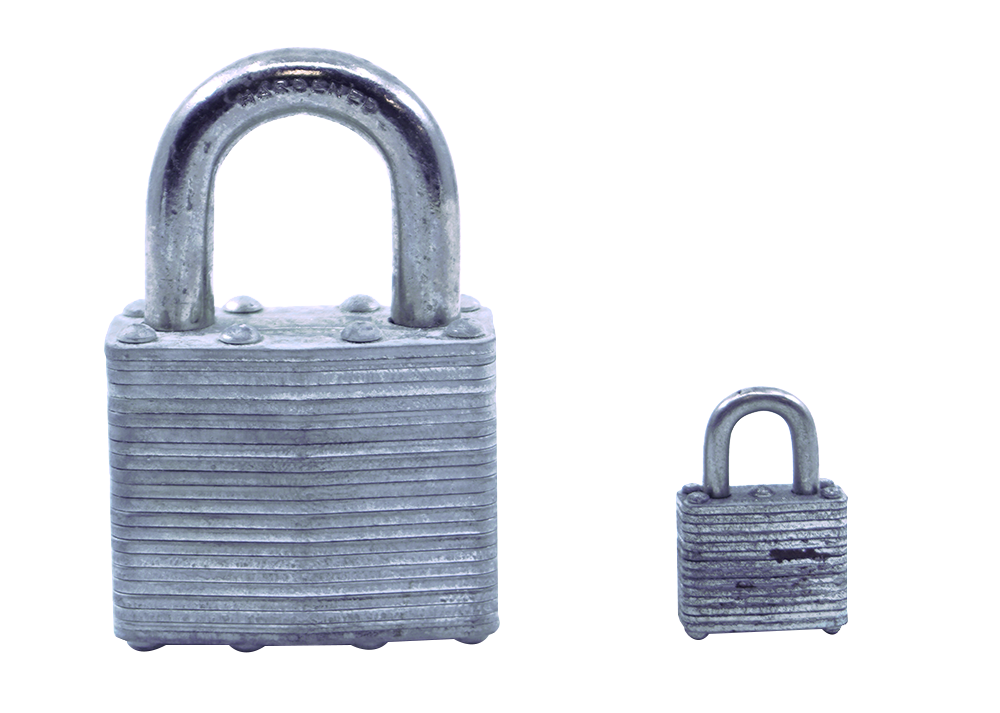

I used a simple principle called lamination. I took the idea from looking at how bank vault doors and war ships were built and imagining it in miniature for a padlock. For the padlock design, I layered identical pieces of metal, stacked on one another like a multi-layered cake. Those layers were then pressed together very tightly and riveted together. The technique allowed me to use small pieces of metal and even scrap, which I could get at a really low price, while creating exceptional strength, durability, and consistency. It was a good design and I tried to sell it to a few manufacturers in the area, but no one was buying it. They all thought it was too complicated or too heavy. I disagreed.

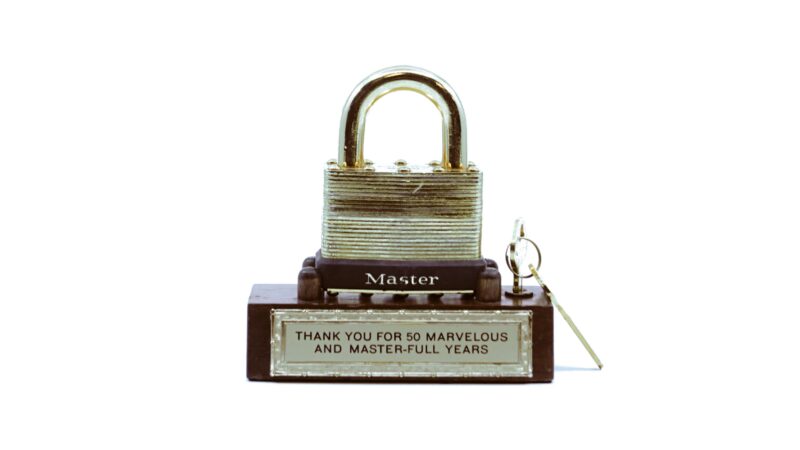

Thankfully, a couple of my good friends were on my side and with their help we started our own company. We called it Master Lock.

Five people, a drill press, a punch press, and a grinder in the basement of a building on Water Street. That is all we had when we started. But the locks were so good that we grew in a hurry. Before too long we had to move into a bigger basement. And then we took over the whole building—all five floors.

For someone like me, having a manufacturing operation on five floors is an absolute embarrassment. I couldn’t stand the thought that the good people who were working for me were in a situation that wasn’t optimal. Of course, my mind was on efficiency, but it was also with the well-being of my employees. We were all in this together and I didn’t want anyone who was working with or for me to be put in a situation that made them uncomfortable.

So much of what I did as a business person was evaluated by the numbers, the big and flashy promotions, or the profits. But, what always interested me the most was making people feel like they contributed to an organization that cared about them. Sometimes this was met with resistance or awkwardness. My factory was populated primarily by women, for example. I thought it was important to provide good working opportunities for ladies of the city to have access to a living wage. When WWII hit and so many women flocked into the workforce, my business was already predominantly female. It seemed strange for some on the outside, but it made the work environment much better for all involved. It was also strange for some people on the floor to call me Harry; most had been trained to call their boss Mr. This or Mrs. That. I always wanted to be known as Harry, and I wanted my employees to feel like they could come to me as they would a friend.

Other comfort-oriented initiatives were more immediately welcome. I invented a system for assemblers to sit in one spot and have all the needed materials come to them. It was important to me that each lock was assembled by the same person rather than in an assembly line; yet I didn’t want people to have to stand and move around the room to get what they needed. Instead, I took the idea for a Lazy Susan and expanded it. People would sit in their chairs in front of large round disc-like desks. Every piece that was needed would be loaded on in clockwise order. So to add the next layer or item to a lock, the assembler simple had to spin the disc to their left and the needed piece would spin right to them.

I also decided to air condition the factory floor. It occurred to me when the air system installers were in our executive offices, talking through logistics. As I looked through the window at those hard-working people below making the locks that made us all a living it seemed wildly unfair. I asked them how much it would cost to cool the whole factory rather than just the offices. They scoffed at the price and the idea, but I had already made up my mind. I would rather have my suits do the sweating. Now, don’t get me wrong: I love the big, flashy things too.

Once, my company sent 147,600 padlocks to New York City in a single train car to lock up all the bars during prohibition. It was a bit of a marketing stunt, but that era was very good to our company and we grew substantially throughout the late 1920s and into the 30s. I always believed that I was in a recession-proof business. When times are good, people have lots of things that they’ll want to lock up. And when times are tough, people want to lock up what little they have.

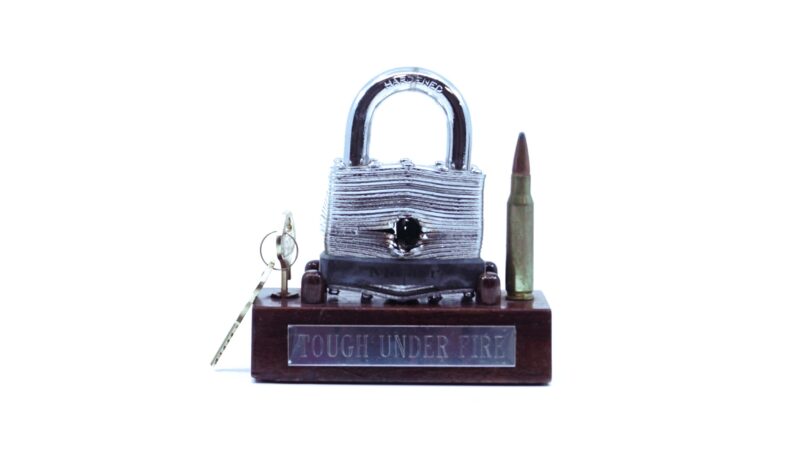

Another marketing stunt came many years later–long after I was already dead and gone. We knew that our design was built to withstand even the most brutal assault, so we put it to the ultimate test by having a marksman fire a bullet through the lock to see if it would still stay secure. Sure enough, it did. It made for a great television commercial. People were flabbergasted. It seemed like magic that something could have a hole put through it and keep on working as intended.