Golda Meir

The plane is buzzing with people. They keep coming up to me, “Is this right Madam Prime Minister?” or “My contact is telling me this Madam Prime Minister.”

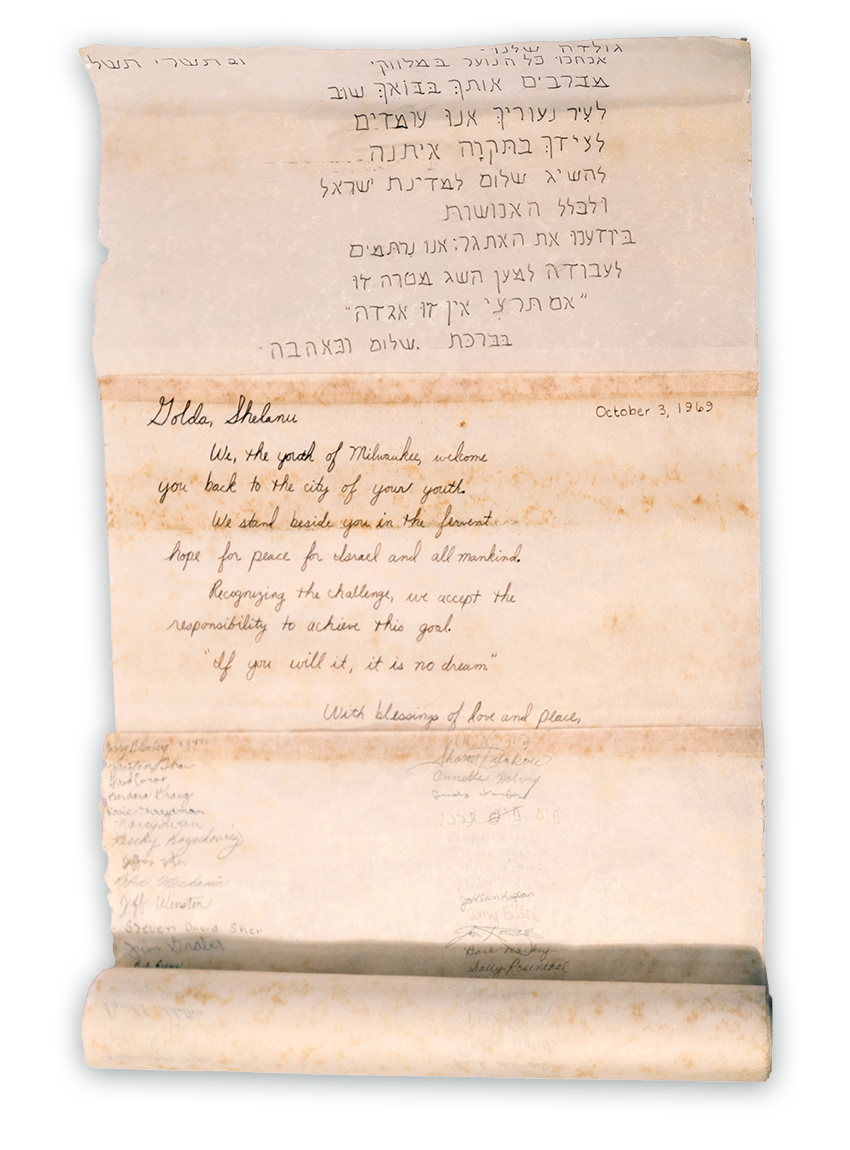

I am amazed by my schedule during this upcoming visit, my first to my American hometown as prime minister. Meeting a delegation and speaking at the airport, visiting my first school, 4th Street School, and addressing the community at the Milwaukee Theater. Eight-year-old me could never picture this old lady coming back with such fanfare. But that girl knew she wanted to be more than a young mother and she knew that education was the best way to find my path.

As the noise of the busy plane fades into the background, I think about an even younger me, my first arrival in Milwaukee, and all of the things that led my family here in the first place. The plane is buzzing with people. They keep coming up to me, “Is this right Madam Prime Minister?” or “My contact is telling me this Madam Prime Minister.”

Everything in my early life was about movement and challenge. My father, a skilled carpenter, had special dispensation to work in Kiev, outside the Pale of Settlement. Being in Kiev was both a grand opportunity and a geography of uncertainty. My father’s skills were valued, until a building was built and then he was out of work again. So, he was constantly looking for opportunities. I remember a series of apartments in different areas around the city; I remember my father’s excitement over certain opportunities being regularly stained with failure and disappointment. Our family was growing, but was also stricken by death. There were three of us children: Sheyna (b. 1889), me in the middle (b. 1898), and Tzipke (b. 1902), the much-petted baby. There were five other children born in those years who died as babies of infections and diseases. There was also a lot of fear. We never knew if there might be a pogrom, which was so common in the Pale. And we wondered if it wasn’t outright violence, was antisemitism preventing my father from stable work? When Tzipke was no more than six months old, my father decided to go to find his fortune in America. This became my first big move to another city, Pinsk, where my mother’s family lived.

Pinsk was more stable than Kiev, but there were still so many challenges. For one thing, the fear of pogroms followed us even into Pinsk which had a much larger Jewish population. For another, my beloved sister Sheyna started organizing anti-tsarist meetings in our house. And she was dating a fellow revolutionary, Shammai Korngold. When my father wrote in 1905 that he had scraped together enough money for us to join him in this place called Milwaukee, my mother jumped at the opportunity to leave. Yet another long journey, which was itself riddled with challenges.

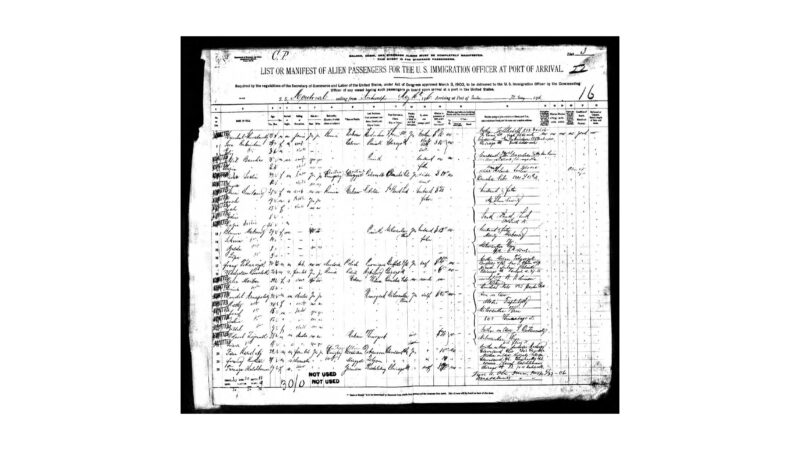

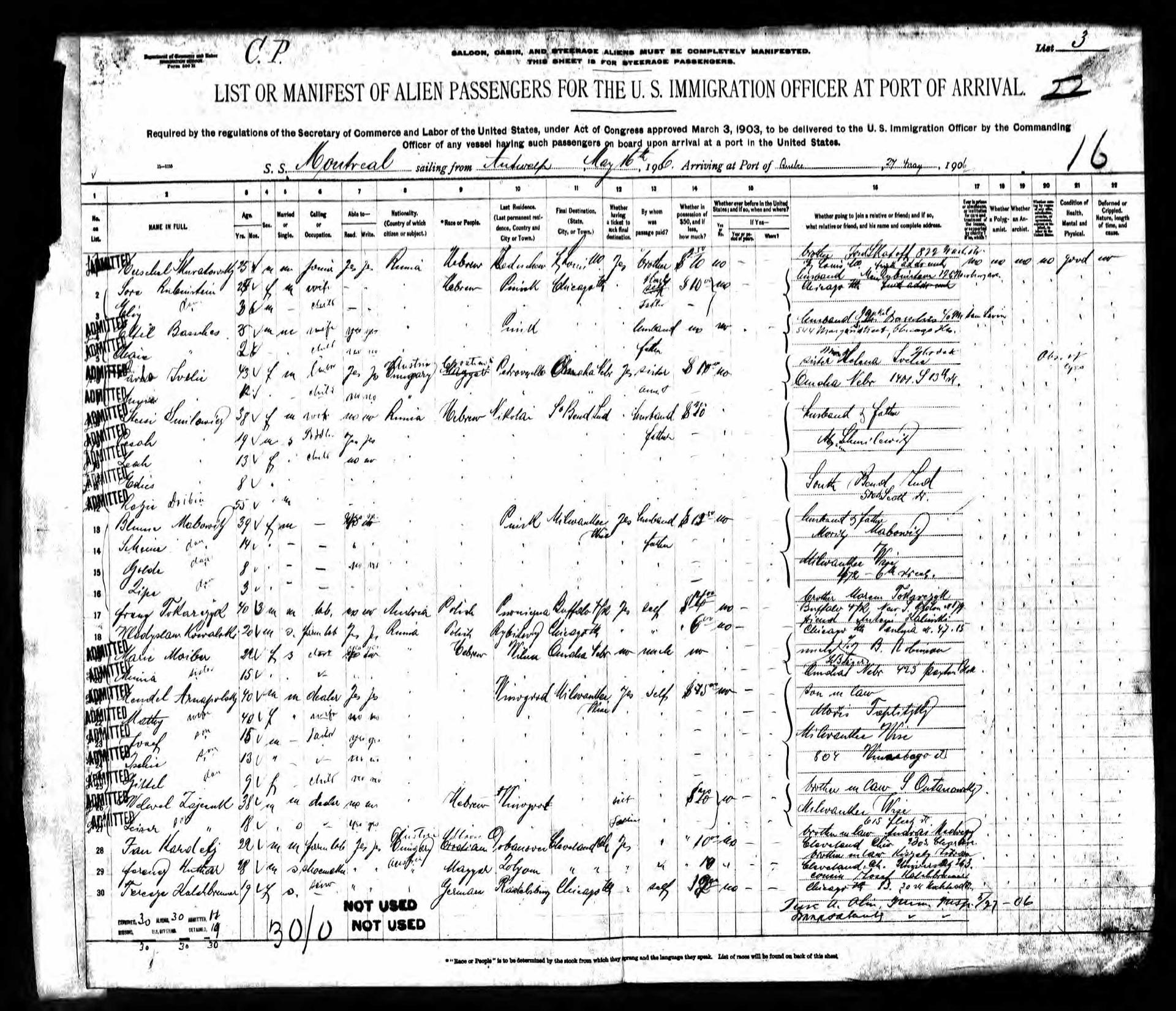

You see, when he left us in 1902, my father didn’t have enough money to pay for both his passport and the ship’s passage; so a women with three children paid him to use our names and traveled as if they were Bluma, Sheyna, Golde, and Tzipke Mabovitch. This meant that when it was time for us to immigrate, we didn’t have passports to use! We left Russia with false papers, sneaking across the border to Poland. I was eight years old and I had to pretend to be five (luckily I was small for my age) and Tzipke had to pretend to be with a different family. We took a train to Vienna, Austria, and then to Antwerp, Belgium where we boarded a boat and could finally use our own names again. It was not a pleasure trip, that fourteen day journey aboard the ship. Crammed into a dark, stuffy cabin with four other people, we spent the nights on sheetless bunks and most of the days standing in line for food that was ladled out to us as though we were cattle. Mother, Sheyna and Tzipke were seasick most of the time, but I felt well and can remember staring at the sea for hours, wondering what Milwaukee would be like.

We landed in Quebec and took a train to Chicago and then on to Milwaukee. When we arrived, I saw father for the first time in four years. He looked like a whole new person— dressed differently with a clean shaven face. This was not my only new experience in my new city. Our first stop was to Schuster’s Department Store, where Father set about trying to Americanize us as quickly as possible. While I was thrilled by my new dress, Sheyna was not as enthusiastic. She had been wearing black in mourning for two years, since the death of Theodore Herzl. This became the first of many fights between father and Sheyna. In general, I thought Milwaukee was wonderful. Everything looked so colorful and bright, and I stood for hours staring at the traffic and the people. The automobile in which my father had fetched us from the train was the first I had ever ridden in, and I was fascinated by what seemed like the endless procession of cars, trolleys and shiny bicycles on the street.

Sheyna wasn’t the only one who fought with our parents. For me the fights were always about education, and it started almost immediately when we arrived in Milwaukee. My father could never make enough money to support us, so mother opened a grocery store in the front of our apartment. She expected me to stay and watch the store while she walked down to Commission Row to get more food to sell. This made me late to school and sometimes I missed it altogether. It was so frustrating—I just wanted to go and learn, but my family needed this money. My parents never fully understood the value of an education for a girl, but I kept fighting.

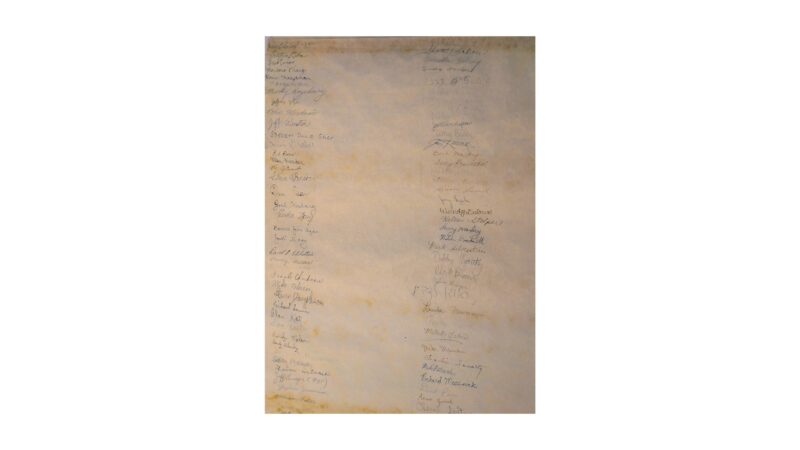

And this fight wasn’t just for me. I noticed that other children faced different challenges in going to school. When I was eleven I saw other children attempting to learn without books because their parents didn’t have the money to buy the textbooks they needed. I brought together my girlfriends, all of whom came from similar impoverished circumstances, and I said we need to make a difference. Starting off, we put three cents of our pocket money into a general pool every week; but we knew at that rate, we would never have enough money. So we organized fundraisers and drives. We hosted a performance at Paschen’s Hall and used the money we generated to buy fifteen textbooks! This meant fifteen children could suddenly take ownership of their learning. The success of the event and the mission behind it generated a little press and I found myself in the paper. I loved it and knew it wouldn’t be the last time; and nowadays, I have journalists constantly swirling around me.

After finishing Fourth Street School, my parents and I had another big fight. I dreamed of becoming a teacher, which was a big dream for an immigrant girl. It meant more schooling than my parents thought necessary. Since I had graduated from eighth grade, I had learned enough, in their view. They suggested I take a secretarial course and become an office worker. Despite their reservations, I enrolled myself in North Division High School, but I knew that this was only a short-term solution. It was only a matter of time before I had to quit school.

It wasn’t just schooling that stood between me and my mother, it was also marriage. By the time I was a young teenager, she was ready to marry me off to Mr. Goodstein, who was more than twice my age! He said he would wait for me, but what would this mean for me and my dreams of education and independence? Sheyna and I conspired together and planned for me to escape. She already lived in Denver and I decided I would run away, escape this looming marriage, meet her in Colorado and continue my education. Another long journey stood before me, this time all by myself.

On a cold February evening, I lowered my small bundle of clothes to my friend Regina who dropped it off at the train station. The next morning I got ready for school as usual but went to the train station. I was so green—I didn’t read the schedule and had to wait all day to leave, each moment was more terrifying. What if my parents read my note “I am going to live with Sheyna, so that I can study” and came after me. Luckily this didn’t happen and I made my escape.

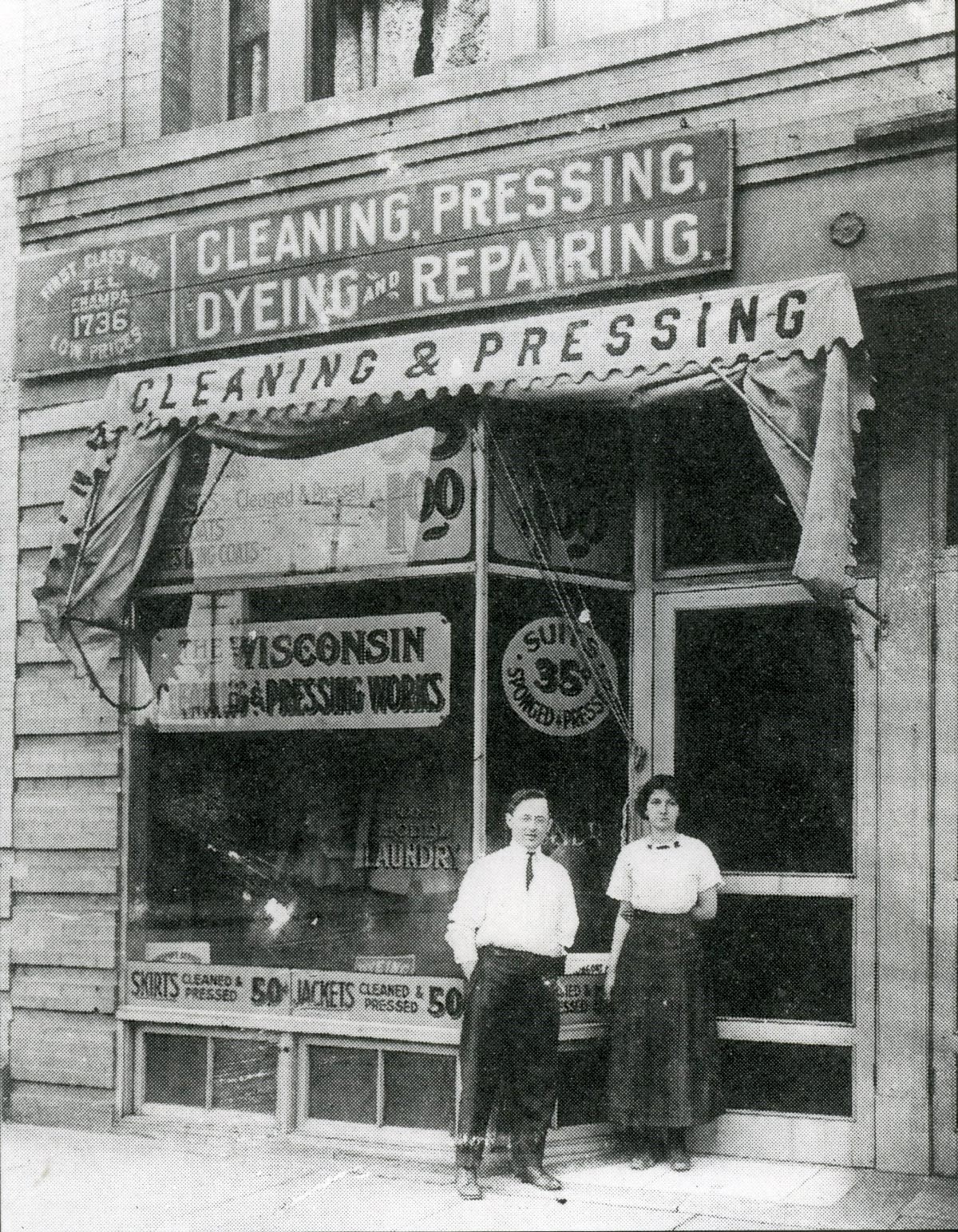

Sheyna lived in a two-room duplex with her husband Shamai, the same revolutionary she had fallen for years earlier in Pinsk, and their baby. My days were busy—I walked almost two miles to North High School for classes, then ran to help Shamai with his dry-cleaning business so he could go to his second job as a janitor. Sheyna had maintained her political fire, bringing together a community of anarchists, socialists, Zionists, and communists around her kitchen table on a regular basis. Listening to these conversations opened up a whole new world to me, one that my sister didn’t always think was appropriate for a teenage girl. She only allowed me to stay up for these discussions if I promised to clean the cups afterward. This experience became the bedrock of who I am today and these critical, radical thinkers introduced me to Zionism and cultivated my passion for a Jewish state in the land of Israel.

It was also in Denver that I met my future husband Morris Meyerson. We were opposites in many ways. He was quiet and artistic, I was extroverted and politically minded, but from him, I learned all the beautiful things. Sheyna didn’t approve of this relationship and she tried to control my every decision. So, I found myself running away again, this time to establish independence from my sister who had once freed me. Around this time of confusion, I received a letter from my father telling me that my mother needed me. So I left Morris and my life in Denver and came back to a very different home life in Milwaukee.

My mother, who was running a deli, now had a thriving business. Our apartment was larger and we had a piano on which Tzipke– who was now called Clara–took lessons. My parents conceded on schooling and I enrolled at North Division High School. In the time I was gone, their world had expanded: they had begun hosting speakers, Yiddish writers, Jewish organizational leaders, and people visiting from Palestine raising money for Jewish settlement there. The vibrancy of Sheyna’s kitchen was replaced with the unexpected dynamism of my parent’s house. Father and I started working for these causes, focusing our efforts on raising money. I became active in Poalei Zion and taught at the Yiddish Folk Shule.

When I graduated in 1916, I still believed teaching would be my path, so I enrolled in Wisconsin State Normal School in Milwaukee. I quickly discovered that I was more passionate about organizing for Poalei Zion and soapboxing on the street. I never spoke with notes but would just offer what my audience needed to hear. And with intense hard work and lengthy hours, I was not just known in Milwaukee, but nationally. At some point the dream of teaching lost its shine and I left college.

Morris came to Milwaukee and we were married in my parents’ apartment in December of 1917. I was nineteen years old. I was traveling all over the country speaking on behalf of the Poalei Zion, pushing to build a Jewish state in Palestine. But it wasn’t enough for me. I needed to be there, working on the ground and I was determined to emigrate. I was not alone in this journey. Of course, there was Morris, but also my friend Regina and her husband, and Sheyna and her two children. We moved to Palestine in 1921 and continued to advocate for the creation of a Jewish state.

Finally, the State of Israel was established in 1948 and I immediately served in various roles within the new government. I was the first Israeli ambassador to the Soviet Union, going back to Russia almost fifty years after fleeing. It wasn’t my favorite post and I was glad when it ended after a year and I could start really making an impact as the Labor Minister, the Foreign Minister, and eventually the Prime Minister in 1969.

Over the years, I have traversed Israel and the world, working to create a country. I came back and forth to Milwaukee many times, despite the fact that my family no longer lived there. But this was the place where I became a leader and strengthened my ideals. While my drive and stubbornness were intrinsic to me, Milwaukee provided me a way to direct them and the education to know what to do with them. I still love the movement of living. Maybe it comes from my earliest days, following opportunities wherever they presented themselves. I do the same now, but for the benefit of more than just my family. I do it for the benefit of all Jewish people.