Jack Marcus

I was a happy thirteen-year-old. When I celebrated my Bar Mitzvah in my small town of Radziejow, Poland, I could never have imagined my future.

I was an only child. I would help my father – a glass cutter – with his work. My mother doted on me. My grandfather, a tailor, taught me how to sew. My uncle gave me a bicycle, and I happily rode all over town. Then, the Nazis came.

I learned a survival skill early on that would stay with me throughout the war. For the Nazis, if you don’t prove your value to them, they kill you. This was the key to my survival.

When the Nazis first came to Radziejow, they wanted Jewish workers who could slave for them at a nearby labor camp. My father was not healthy, and although I was just fifteen and not old enough to work, I went along to take care of him. The Nazis barely fed us. I would sneak out before dawn to find food for my father. A kind Polish farmer helped me, giving me enough to nourish my father and keep him strong. Eventually, the Nazis realized I was too young to work in their labor camp. Against my will, I was sent back home. Soon after, my father died.

Then, a terrifying order came. All Jews were to assemble in the town square the next day. My mother knew just what that meant. I couldn’t imagine.

The next morning, my mother packed a bundle for me, with some clothes and food. She told me to run. I didn’t want to leave her. She forced me, saying, “Run, Itzek, run. Maybe you’ll be one of the lucky ones.” What did that mean? The Nazis arrived. They were everywhere. I ran to the outskirts of town and burrowed deep inside of a haystack. Then I heard them. The Nazis were walking around the haystack, searching for Jews, searching for me! I froze. They moved on. My first brush with death.

Only later did I learn what happened to my mother. She was taken along with the Jewish women, children, and elders, from the town square to the big church, where they were locked for a full day and night. The next day, my mother and the other Jews from my town were loaded into trucks with the engine exhaust piped into the back. By the time they arrived at Chelmno, they were dead. The Nazis buried them deep in the forest in a mass grave the size of two football fields. To the Nazis, they were worthless.

From that haystack, I made my way back to the labor camp where I knew I could find my aunt and uncle. I was just fifteen, so I made myself look and act older. I worked. I survived.

Eventually, we Jews were absorbed into the expanding Nazi war machine. We were transported on overcrowded trains to concentration camps, where we were put to work in their big factories. They had rows of barracks, and we slept body-to-body on wooden shelves. We were barely fed. We were stripped of all human dignity. We were tattooed on our arms with a number. I was no longer Itzek Markowski. To the Nazis, I was “144346.”

When I arrived at Auschwitz, I was ordered to the line with women, children, and elders. There was another line with men, who I realized, could be laborers. My mother’s advice came back to me. “Maybe you’ll be one of the lucky ones.” In the chaos of the moment, I found a way to sneak out of that line, which led to death, and make my way to the line of men. Always pay attention.

I was assigned to work in a steel factory. Every day, we trudged for miles back and forth from the concentration camp to the factory. There was little food. We lived only to survive.

Then, one day, a steel girder in the factory fell on my foot. Throbbing pain! I was taken to a hospital where my big toe was amputated. There was no anesthesia. Ten days after that brutal surgery, I was warned that after 14 days, the Nazis would kill me if I couldn’t go back to work. Even though my wound was raw and painful, I went back to work. A kind Jewish doctor, assigned to take care of us prisoners, offered to clean my wound and help me at the end of each day. He saved me.

There were times I was ready to give up on living. One day, I was about to run towards the barbed wire, where I would have been shot by Nazis. All of a sudden, I heard my mother’s voice. She said, “I am with you, and you will have a good life. You are going to survive.” I felt her with me, and I did not run.

There were times I was ready to give up on living. One day, I was about to run towards the barbed wire, where I would have been shot by Nazis. All of a sudden, I heard my mother’s voice. She said, “I am with you, and you will have a good life. You are going to survive.” I felt her with me, and I did not run.

During those dreary days in Auschwitz, I figured that I had to do more to survive. Thankfully, as a child, I was taught how to sew. I found a cap, some material, a needle and thread. I took the cap apart and made a pattern. I cut the pieces of material and carefully sewed them into another cap. Then, I found a Nazi who wanted a cap. We did a trade. He got the cap, and I got my survival – bread, cigarettes to trade, or whatever could keep me alive. I felt a taste of independence. This is something I could do to save myself.

Eventually, the tide of the war turned. The Nazis had no choice but to retreat. Our slave labor was needed back in Germany, and we were herded onto open railroad cars for the long trip from Auschwitz to Dachau. It was January, 1945. There was no roof, warm clothes, food, or water. All we had to drink was the snow that fell upon us, shivering in the frigid air, as the train trudged forward.

Every so often, the train would stop. Kind villagers would toss loaves of bread at us. At each stop, the bodies of those who died would be thrown off the car. The situation grew more and more desperate and hopeless.

At one stop, a pile of bodies – those who died among us – were heaped on the ground beside our rail car. A boy I befriended asked a Nazi if he could fetch a coat from one of the bodies. The Nazi granted him permission. The boy jumped down and as he bent to take the coat, the Nazi stood behind him and shot him. The boy died on the pile of bodies, and the Nazis laughed. This was their cruel entertainment. This is what life had become.

With that, I lost hope. There was no way I could survive this frozen torture. Death was better.

At the next station, villagers again tossed bread at our train. One loaf hit the side of the car and fell to the ground. I looked at the bread and I looked at an older Nazi standing below. I knew that if I jumped to grab the loaf, I would be killed instantly. I didn’t care anymore. I jumped and picked up the bread. The Nazi stared at me, and I stared at him. Time stopped.

Instead of keeping it, I threw the bread up to the starving people. I did the unexpected. With that gesture of my generosity, I became a human being to the Nazi. I roused something in him, and he couldn’t kill me. So, he hit me with his gun, and ordered me back on the train. Human to human, unexpectedly.

I climbed back on the train. By then, the bread was already eaten. Somehow though, I regained my determination to survive. I found what I had lost: Hope.

I felt that things were changing. The Germans were in retreat, and perhaps the war was ending.

We were forced to march towards a big warehouse. My friend Max overheard the Nazis’ plans– they intended to shoot us in the forest nearby. Three friends and I decided to make a run for it. We snuck out of the warehouse, and instead of running into the forest, I suggested that we walk calmly on the open road.

We came across a checkpoint, and told the Nazis that we had been freed. A lieutenant ordered a soldier to bring us to town, and if no one would take us, to “make a short process”. To kill us. How could I make it this far, with the war ending, to die now? We got to the empty town, and they spotted a Nazi with two Polish prisoners. The Nazi wouldn’t take us, so in Polish, I begged one of the prisoners. I told him that we’d be shot if the Nazi wouldn’t take us. The Polish fellow convinced him to take us. We marched to Dachau.

The next day, the American soldiers arrived to liberate Dachau. They gave us food, clothes, and clean water. The war ended. I survived seven concentration camps. For the first time since the war began, I was a free man. Six years had passed. I was twenty-one years old. What was I to do? My parents and community were gone. My three friends and I offered to sew and make caps for the American soldiers. They recruited us to their unit, and we traveled to Vienna. Eventually, I learned that my aunt had survived and was living in New York, and she sponsored me to come to America.

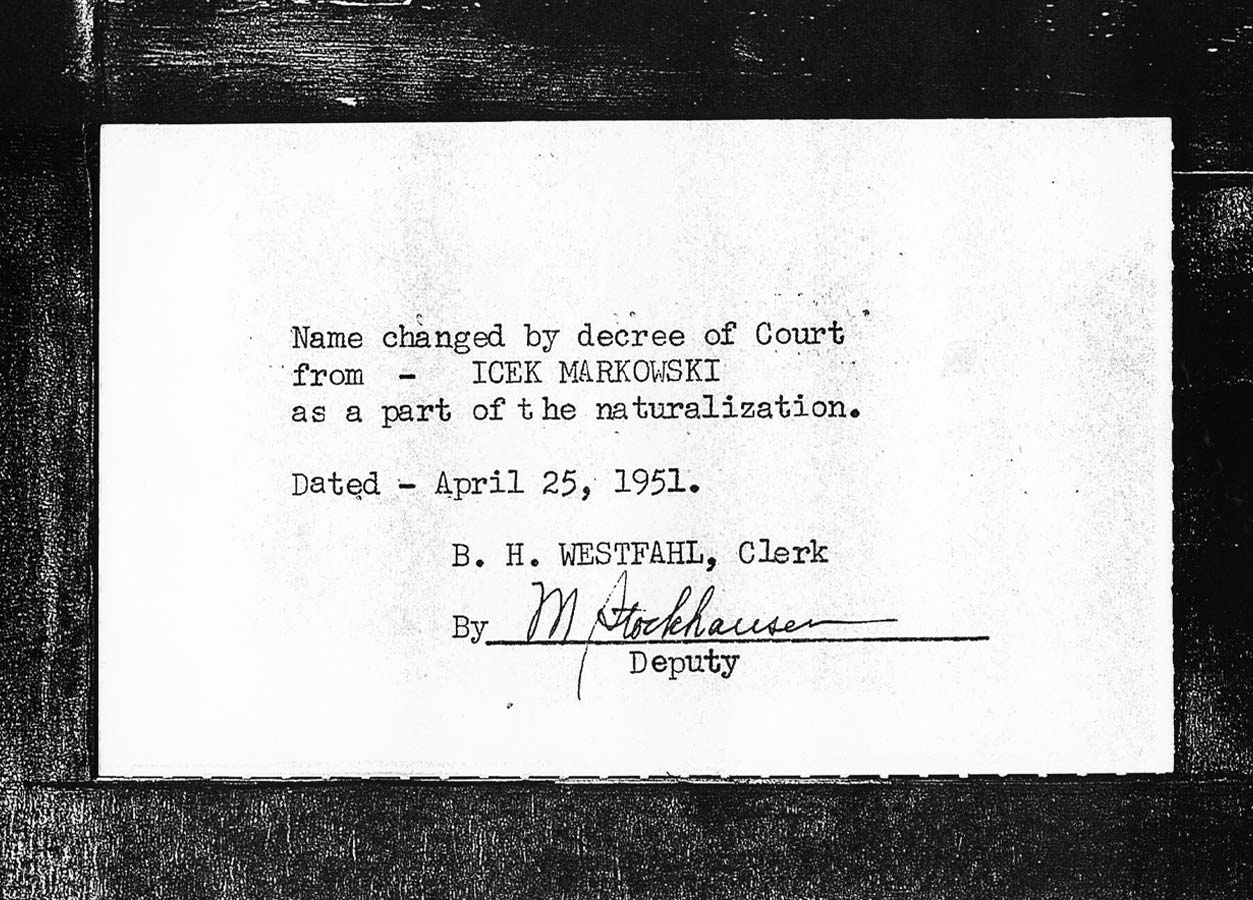

When I arrived in New York, I decided to change my name. I heard that an uncle had moved to England and changed Markowski to Marcus. I turned Iztek into Jack. “Jack Marcus” was my new name.

I then received news that a family I knew from Radziejow was living in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I was invited to visit them. I knew their daughter Marlene from school, before the war. She had learned the ways of America. I proposed marriage and she accepted. Months later, I moved to Milwaukee, and we were married.

Our first purchase was a sewing machine. I would be a tailor. This is how I survived the war. This is how I would support my family.

We had two children. My son Lenny was named after my father. My daughter Sharon was named after my mother. It was a miracle.

I saw a Nazi flag displayed in a home not far from where I lived. That flag screamed at me. It gave me nightmares. I could not let my guard down. I could not tell my story. Even though I lived in America, I was still in hiding. I never forgot the haystack that protected me from the Nazis. I would not let them find me now. My story was my and my family’s secret, and no one could know.

After many years of tailoring, I finally retired. My grandchildren were in school. They encouraged me to come to their school and tell their classmates my story. I took a chance. I got up in front of people and shared what happened to me. The first time I shared my story publicly, I returned to my car and cried.

I learned this was the right thing to do. The secret was over. The world had to know. It was time to tell my story.

Telling the story was my way of making sure that what happened to me, what happened to my family, and what happened to so many millions of people, could never happen again to anyone.

Never again!