Edie Shafer

My story begins long before me, thousands of miles from my birthplace, with a young German-Jewish couple named Gerda and Manfred.

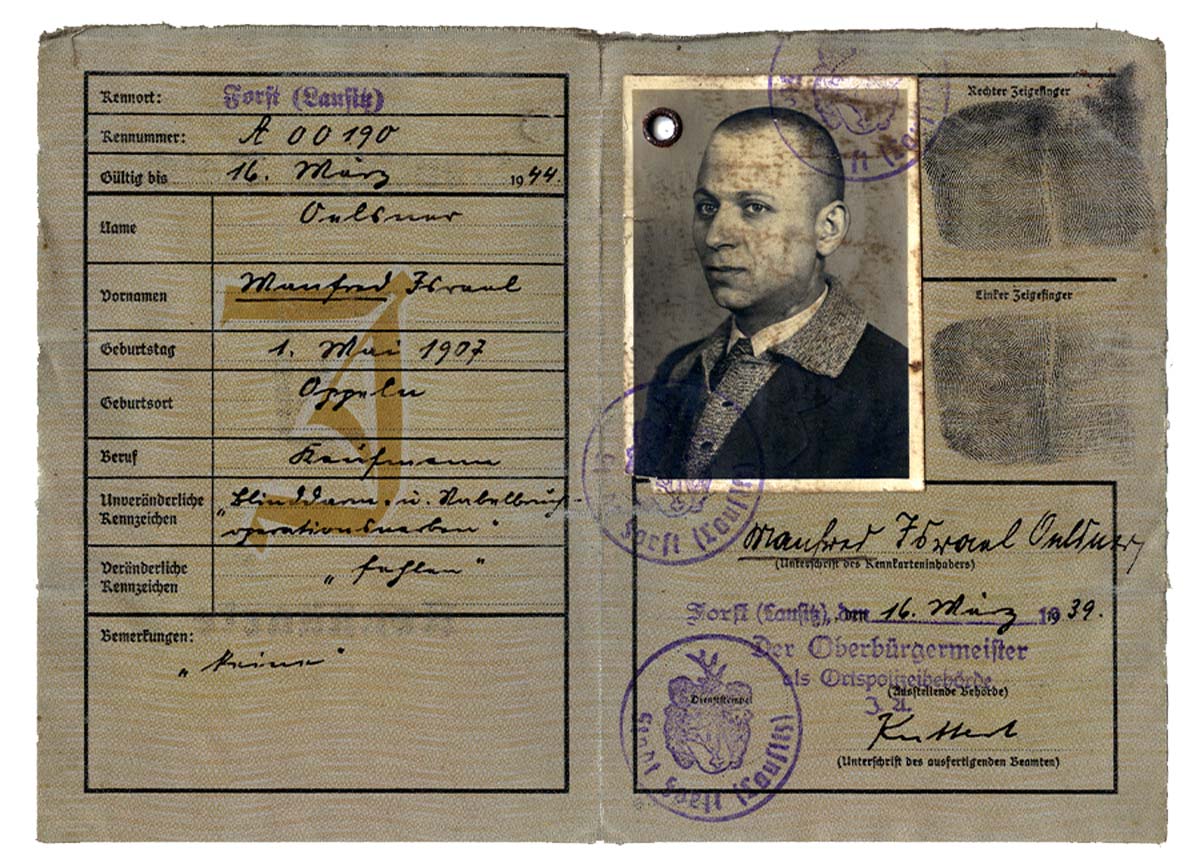

They met in June of 1932, and over the six years of their courtship, Manfred would travel regularly from Berlin to Forst-Lausitz to visit his beloved. After their wedding, they started their new lives together in Forst-Lausitz, where Manfred worked in a bowling alley. They had no idea that everything was about to change.

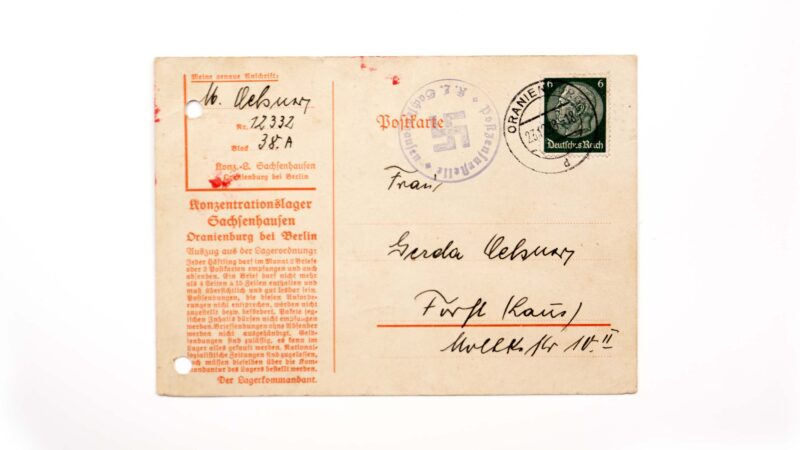

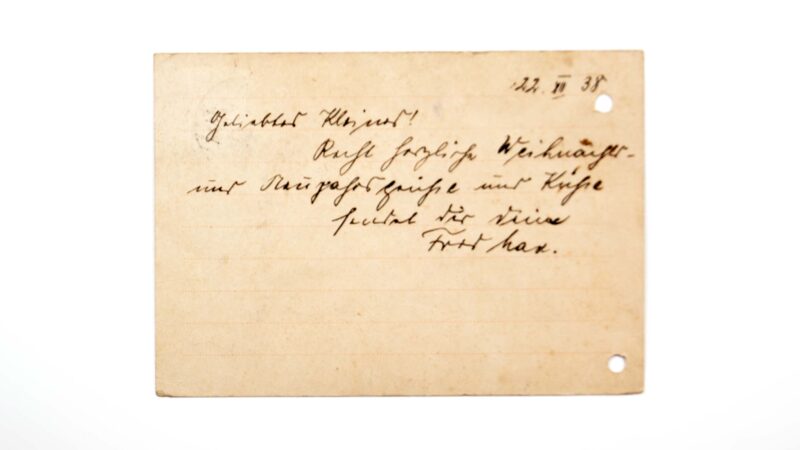

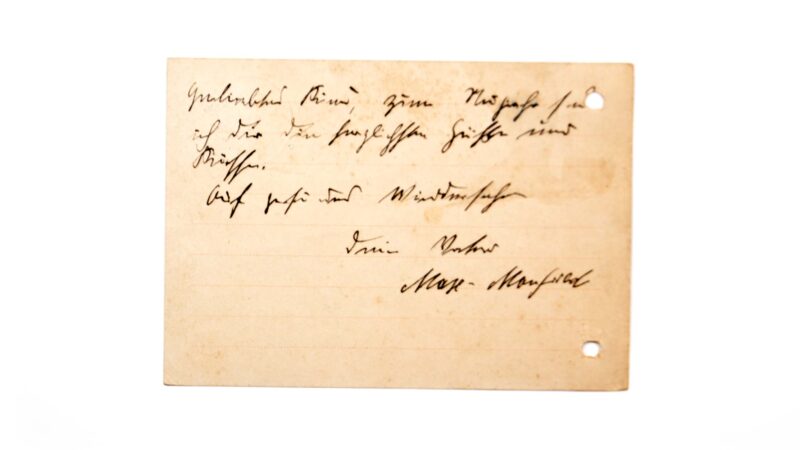

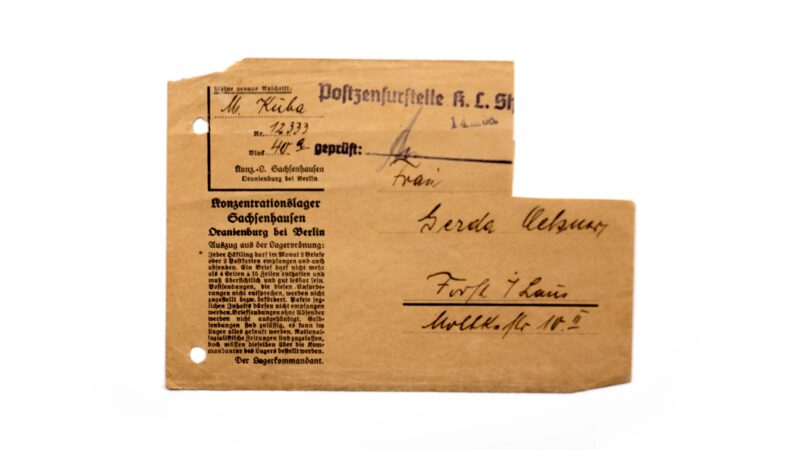

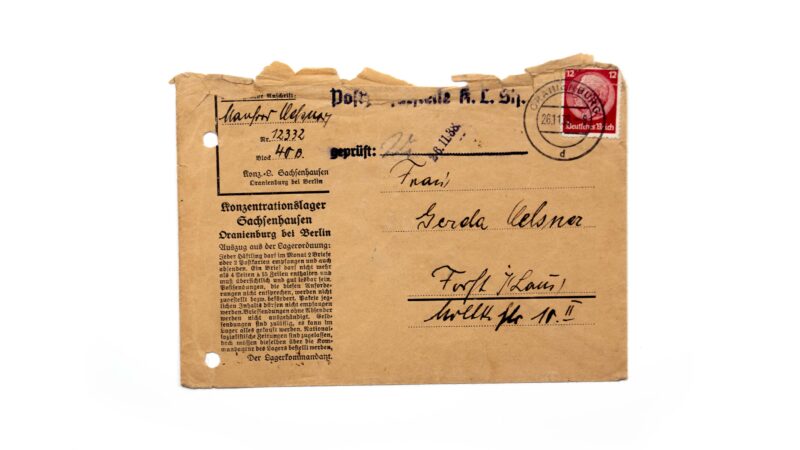

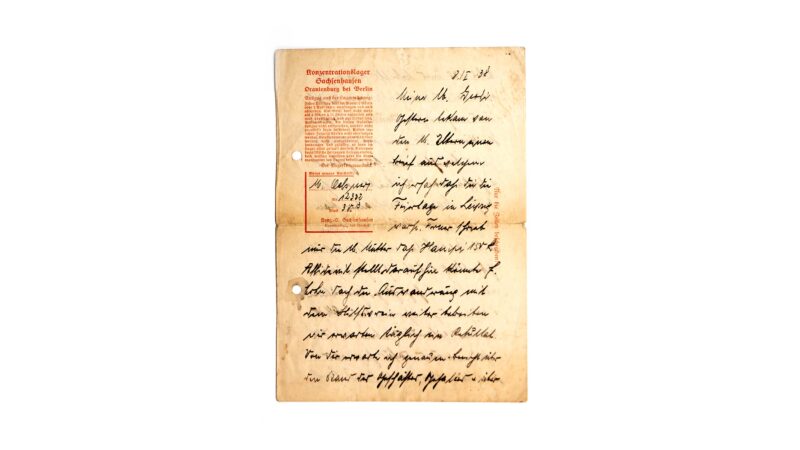

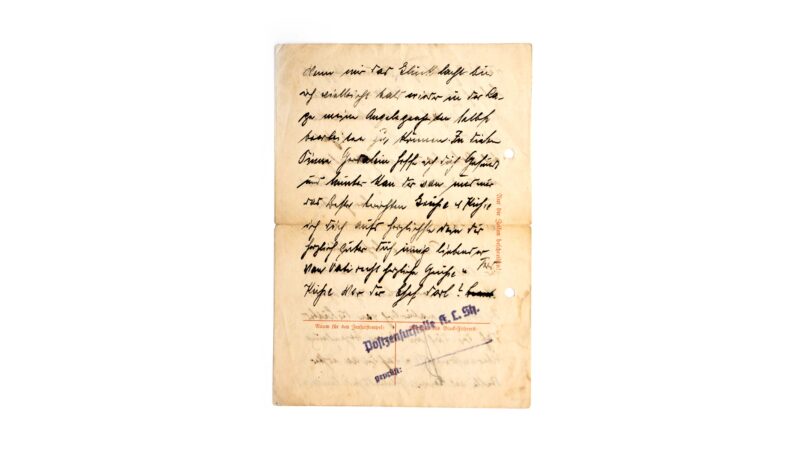

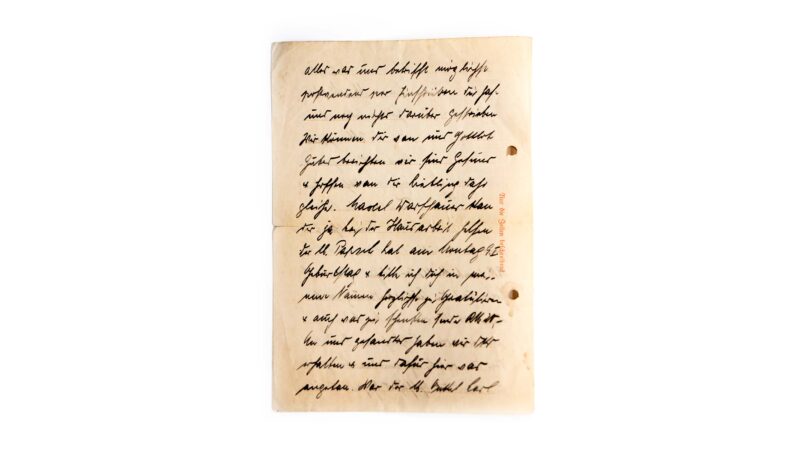

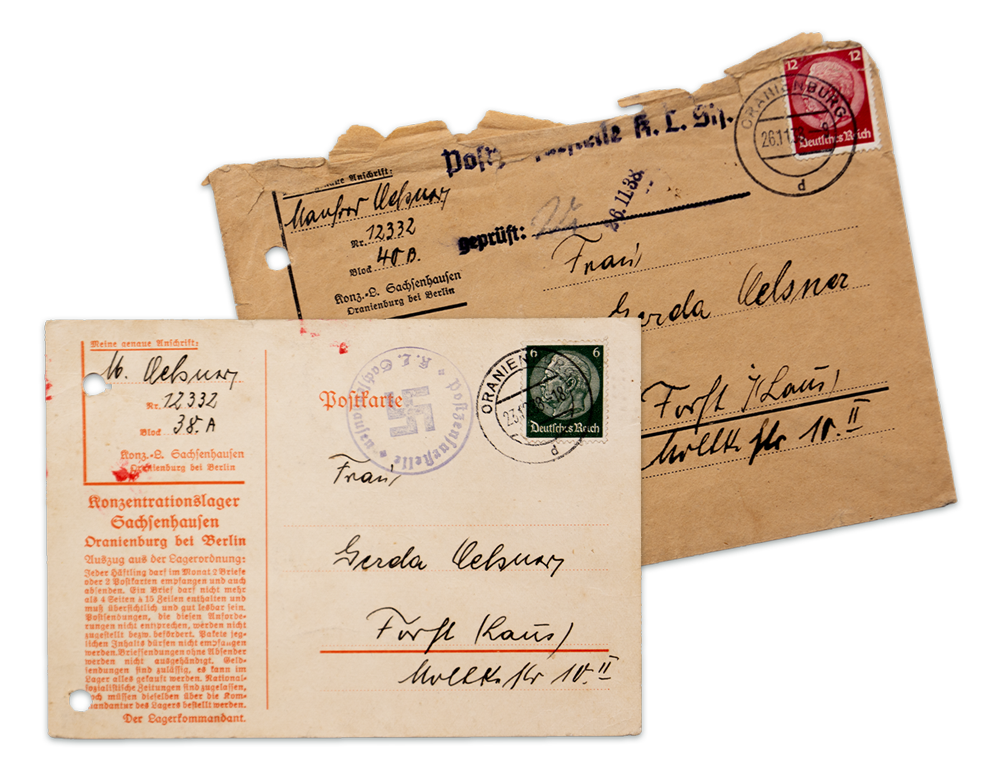

On November 9, 1938, the Nazis unleashed a night of terror against Jews throughout Germany and nearby lands, memorialized as Kristallnacht. During this Night of Broken Glass, thousands of Jewish men were rounded up and taken to concentration camps, and among them were Manfred and his father-in-law, Max. They spent a few days in a jail cell crammed with 8,000 others, surviving off of scraps, before the Nazis transported them to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

At Sachsenhausen, the Jewish prisoners were thoroughly dehumanized by their Nazi captors. They were counted like cattle, given stew without utensils. Without spoons, men wolfed down their meager portions, heads scraping against plates like animals. Manfred refused to be degraded and chose not to eat. When an officer noticed his defiance, he commended Manfred for his bravery and brought him meat sandwiches. Treats like this were incredibly rare, but made all the difference in a concentration camp.

At the start of the new year, Manfred was set free from Sachsenhausen. His brother-in-law in Warsaw was friends with the secretary to the Argentine consul, and got a signed document requesting that Manfred meet with the consul. He eventually used the connection to gain release of Max as well as many others.

On February 7th, 1939, Manfred left the camp and immediately returned to his beloved in Berlin. Yet there was still tremendous danger: The Nazis told him, “The reach of the Gestapo is going around the whole world and we will be watching you.” They gave the couple three months to leave the country forever. After weeks of searching, Manfred visited the Aid Association for German Jews looking for tickets to Shanghai, China. At the end of April, another family couldn’t use their tickets, and the Aid Association paid for them. With no time to lose, Manfred and Gerda seized the opportunity, and traveled from Berlin to Munich to the port city of Trieste. On May 10, 1939, they boarded the Conte Verde, leaving Italy, and all of Europe, behind. It was only then that their new life together could truly begin: in Shanghai, China.

Max, Manfred, and Gerda started their time in Shanghai in a refugee camp called the Heime. The Heime offered a large, barrack-like room with 45 double beds for Jewish arrivals in the Hongkou district. Eventually, the couple moved to a house, where they shared a single room with three other couples and two bachelors (Max had chosen to stay behind at the Heime). They were safe from the horrors of Nazi Germany, yet their lives were hardly easy. Manfred and his father-in-law earned wages by carrying luggage from incoming ships on a handcart, working long hours to survive. On December 1, 1939, they had made enough money to rent a tobacco shop for $80/month. The store measured 7 square feet, with no sewer or toilet. But that store was their livelihood, and later their home, too, as it was safer from thieves than the shared house. The space was hardly big enough for two people to work, let alone live in. But Gerda and Manfred still had plans to grow their family, and soon enough, on January 30, 1941, I was born.

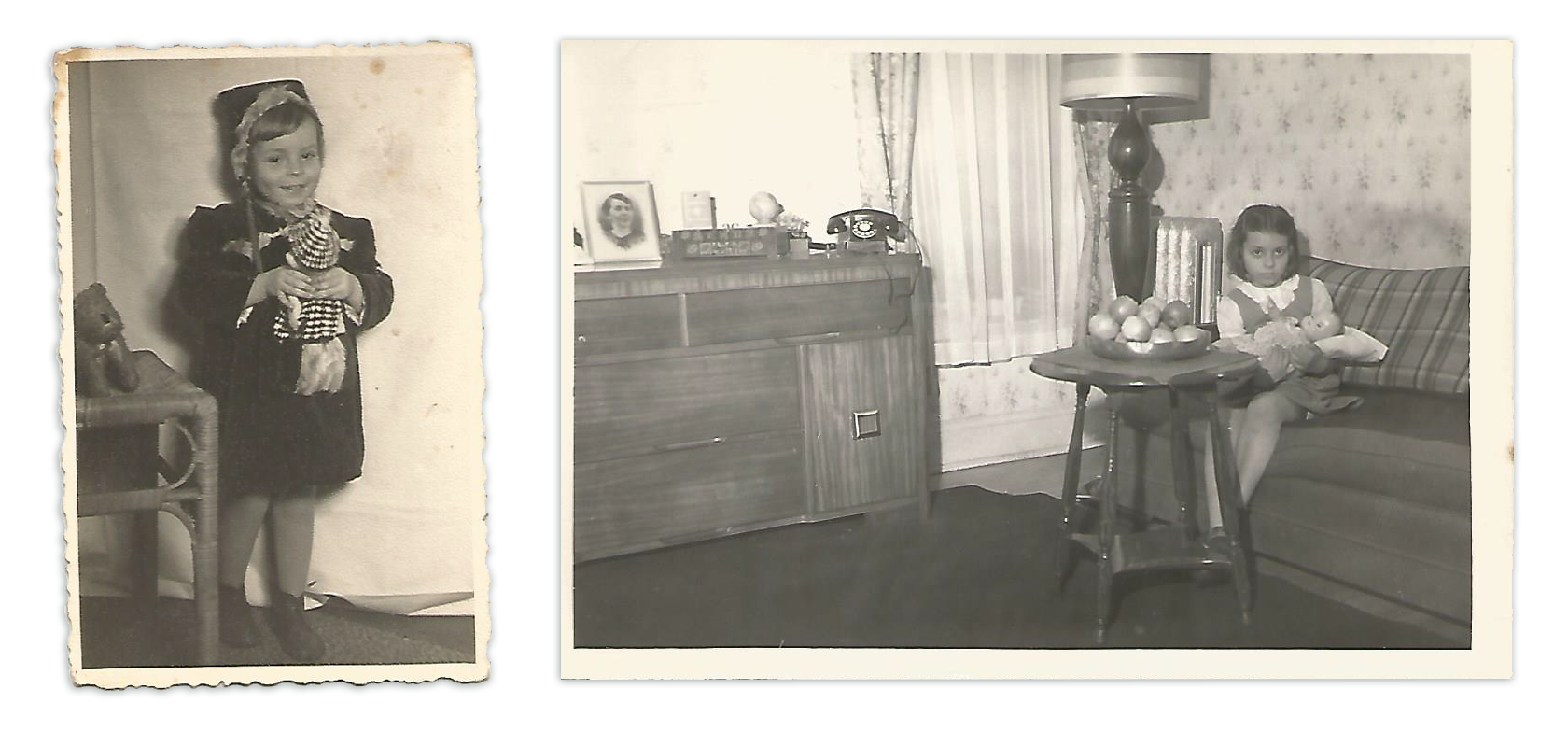

The ghetto of Hongkou was hardly a place to raise a child. The first two years of my life, my parents had me either in the crib or in their arms, for the floor was unsafe for a child to walk on. Given the conditions I once spent over three weeks in the hospital. My father had to donate blood in exchange for my stay.

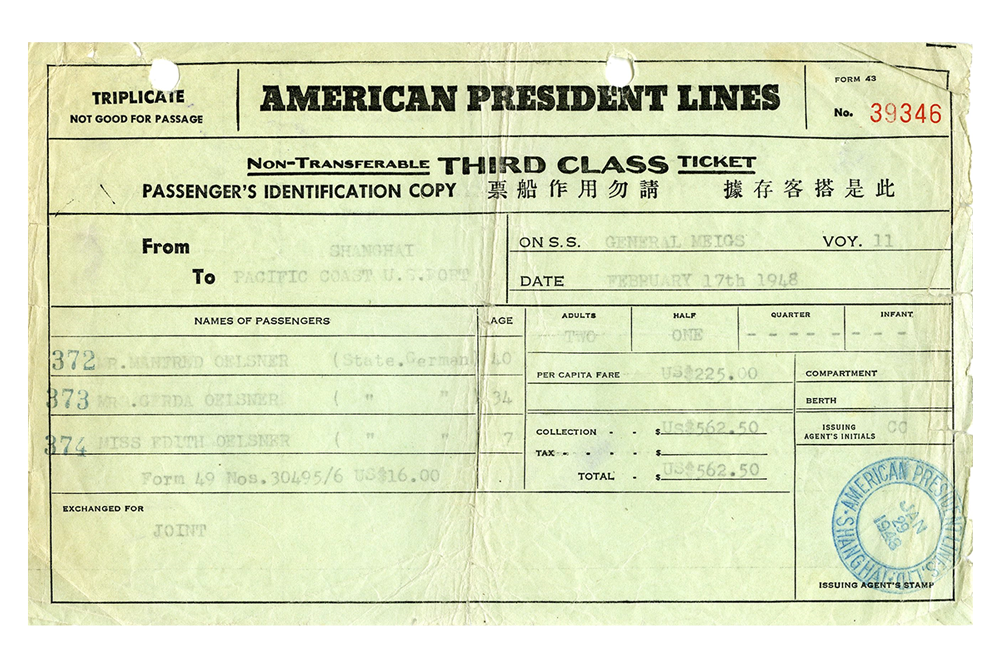

On January 19, 1948, our lives changed forever when we were cleared to immigrate to the United States. We were generously sponsored by Harri Hoffmann, who had fled Germany after Kristallnacht and made his way to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. There, Harri became friends with my cousin Lisset Altman and her family, encouraging him to save our family. Before leaving the country, we received $315 in Chinese National Currency from the American Joint Distribution Committee for “incidentals.” We were so grateful to the JDC for their support.

We left China later that year, and made our way across the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii. I remember our day in Honolulu vividly. We were given lunch and then took a bus tour of Oahu. I was seven years old, but I had never before seen grass, and I rolled around in it in sheer delight. Everything about the soft, green earth represented a tremendous change from the ghetto.

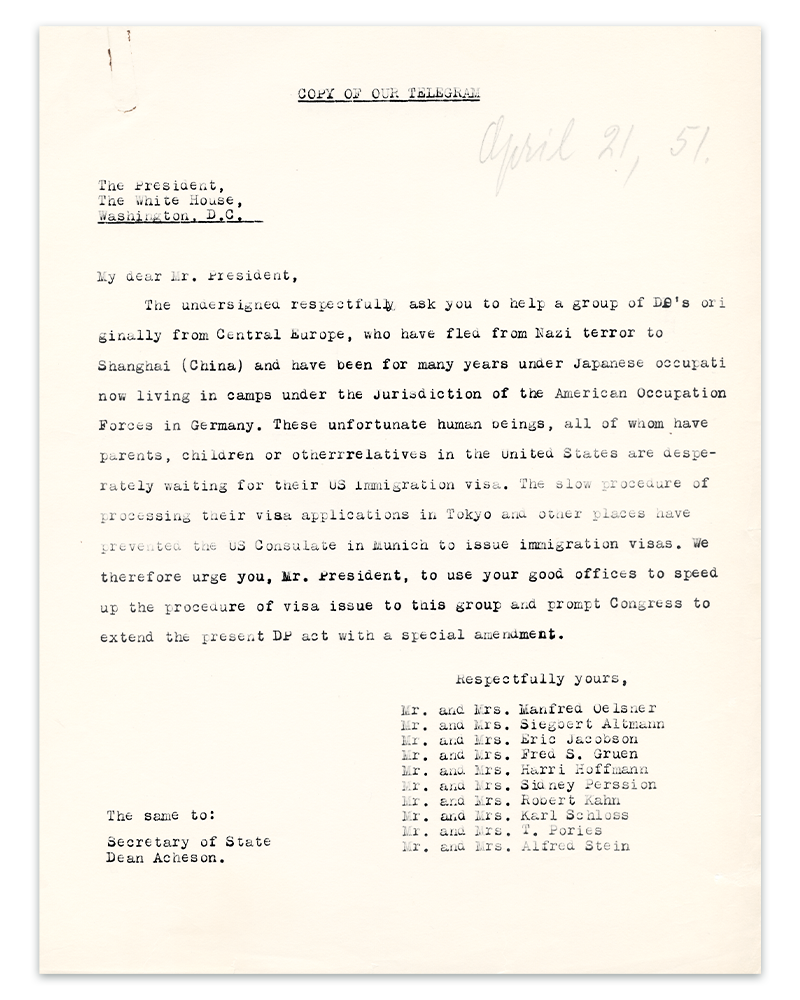

From Honolulu, we set sail for San Francisco, where we first entered the continental United States. My father stayed longer in the city to work, while my mother and I set off for Milwaukee to meet our cousins. Sadly, my grandfather Max had to stay in Shanghai, as he was restricted under a Polish quota. To ease the separation, he gave me a special memory book, which I have to this day. Eventually, Max was able to sail to San Francisco, but the American government put him on a sealed train to New York, and he was shunted back to Germany where he languished in a DP camp. My parents sent 44 letters, 2 telegrams, 2 signature sheets, 3 notecards and countless letters to American senators, governors, and even the President. They were truly desperate. Finally, in 1952, Max was released from the camp, and our family was reunited.

Transitioning to Milwaukee life was not easy for me as a little girl. My father started working in a tannery, and my mother was employed at Shorewood Village Bakery. I had to restart kindergarten, even at seven years old, as the only English I knew were the letters A B C and numbers 1 2 3. I remember going to overnight camp and having a traumatic experience as a foreign girl who only spoke German. Gradually, though, my life improved. I went to college and became a teacher, and met my Neil, whom I married in June of 1964. We had three children together: Joel, Daniel, and Deborah. The years passed quickly; we made our home in Racine, and then back in Milwaukee, and in the blink of an eye, our children found partners and started their own families. Now, I can proudly say that I have 10 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, the lights of my life. My husband of 59 years, Neil Shafer z’l, died in August of 2023. I currently live in a memory care facility in Mequon. Looking back on my story, I know that my family is my greatest gift, and I treasure them above all else.