Lizzie Black Kander

If I’d listen to the men in my life, you’d have never seen this little book. They didn’t think the work I was doing for young women was worth spending time or money on, much less publishing in a book. But I’ve known since a young age that men have a tendency of being wrong.

Even as a teenager, it seemed to me that our country was in a state of disrepair. And this didn’t seem unrelated from the fact that men were running the show. As valedictorian of my graduating class of 1878, I gave a speech outlining my ideas about what could change if I were elected President of the United States. For a highly practical person such as myself, this didn’t seem too far-fetched. I knew then as I know now how to see a problem for what it is and take steps to solve it. One doesn’t need to be a man to do that; in fact, they seem pretty wretched at the task.

It was after writtng that speech that I grew more intimately aware of the problems that were affecting our country. I became a truancy officer in Milwaukee and was stationed in the desolate slums of the Haymarket district. Though mere blocks from my own neighborhood, Haymarket was like another world.

My family, the Blacks, were somewhat prominent. We weren’t supremely wealthy but we had a good sense of how to live and people respected my father who ran his own dry goods store. My parents came to Milwaukee in 1844 and, alongside other German immigrants, helped to build the foundational institutions of this city. At the time, there were a few hundred Jewish families here, but most identified much more strongly with our country of origin or our adopted country. My family actually helped to establish Temple Emmanu-El, a reform synagogue that promoted integration and assimilation alongside upholding religious and spiritual traditions and practices.

The hope and dream of emigration came true for my family. They found greater opportunities than were available to them in Europe and they were able to make their mark on a city they grew to call home.

The folks I was working with in the Haymarket district had a very different story. Many of them came from Russia, from the Pale of Settlement, and made their way here to flee persecution and violence in their homelands. Rather than pursuing an American Dream, they were escaping the Tsarist nightmare. And unlike my family, they were relatively uneducated, poor, and far more orthodox in their relationship to Judaism. I was in their neighborhood prompting children to get to school; but they didn’t have enough to eat, sufficient shelter, or a way to clean themselves. They were living in squalor and an education was the furthest thing from their minds.

The social programs available to these poor souls were extremely limited and no one seemed to be making much headway to ease their suffering. I was concerned on two levels. Firstly, I sought their own well-being. Secondly, I wanted to ensure that their decrepit status didn’t reflect poorly on my fellow Jews. As we know from a simple study of history, in times of social crisis or stress, Jews tend to be scapegoats. The more awful they appear–by no fault of their own, mind you–, the more likely they are to become the object of ridicule.

In the 1890s I worked with various organizations that focused on assisting immigrant women and their children. It was my thought that by helping out women in their home, I could manage to raise the spirit and station of everyone in the community. I started the Milwaukee Jewish Mission with a goal of helping improve sanitary conditions, increase enrollment and attendance at school, and provide women with specific skills around sewing, knitting, darning, and the like. The Mission was housed at my synagogue and it was a success; but I felt there was more to be done.

At this time I was also studying about the Settlement Movement, which emerged in England in the 1860s and caught on here around the time of my high school graduation. The idea was sound, in my mind: put people from a lower class in regular direct contact with people from the upper class, thereby allowing those in the higher echelons to positively affect those further down the ladder. In America, we utilized the tenets of the movement slightly differently. Rather than assuming that poor people would somehow grow invested in their own well-being through absorption, we began to recognize the need for people of means to settle themselves in spaces that were not doing well, so that we could more directly serve the needs of the people as they emerged. Additionally, it was a useful tool for integrating and assimilating different groups into broader communities. This was the change that I felt was needed.

So, in 1900 I consolidated all of my efforts into the creation of the Settlement House. My duties as president were to oversee the fortunes of the venture and contribute somewhat to its offerings. My best and most beloved skill was cooking. I admired all the gadgetry and the new technologies like baking soda. I thought the skill could be quite useful for both women who intended to stay home and for the unfortunate ones who had to seek domestic work out in the world. Of equal importance to me was that sharing cuisine, food customs, and cooking with the hearth-keepers was a fantastic way to endear the American way to immigrants. I felt that in order to rescue these families from their deplorable condition, they needed to adopt the mentality of an American in any way possible.

The Settlement house was a greater success than my previous endeavors. It seemed women were drawn to our methods and we were encouraging immigrant families to more quickly assimilate into American customs and norms. I wanted to expand. But my husband’s business and political connections, who had funded the initial operation and were the predominant members of my board of directors, didn’t seem to understand the value of what I was accomplishing. They thought the services I was providing were adequate and so expanding the programs was unnecessary. ‘Woman’s work’ has always been belittled in this way.

The Settlement house was a greater success than my previous endeavors. It seemed women were drawn to our methods and we were encouraging immigrant families to more quickly assimilate into American customs and norms. I wanted to expand. But my husband’s business and political connections, who had funded the initial operation and were the predominant members of my board of directors, didn’t seem to understand the value of what I was accomplishing. They thought the services I was providing were adequate and so expanding the programs was unnecessary. ‘Woman’s work’ has always been belittled in this way.

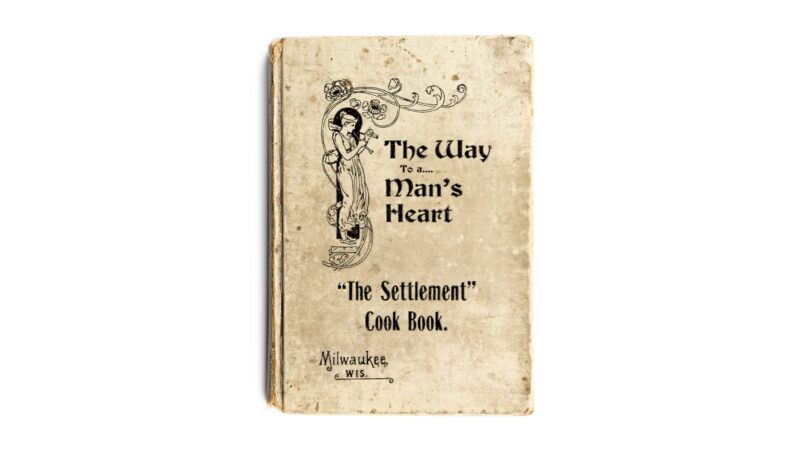

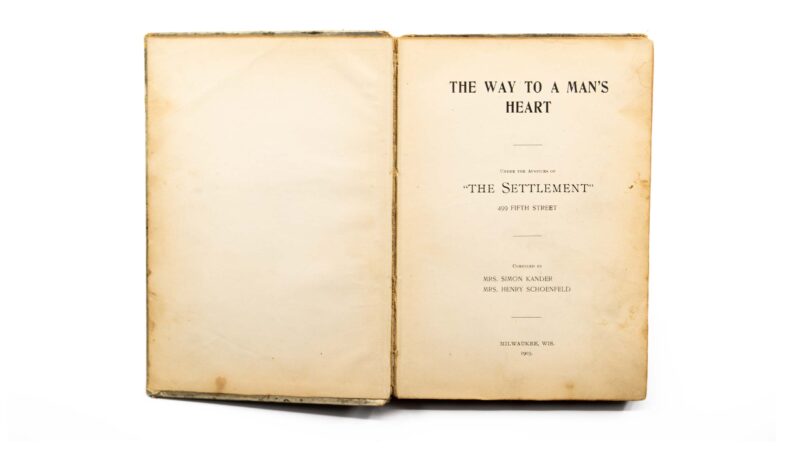

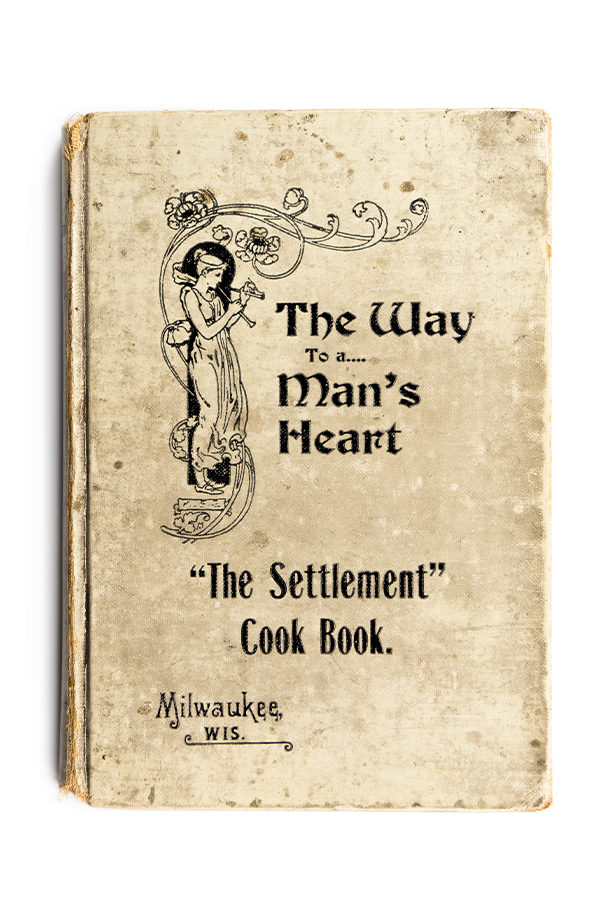

Without their financial support, I needed another way to expand. Since the cooking classes were very popular and at the core of my own mission, I decided to create a fundraiser by publishing those cooking classes in book form.

But again, my all-male board did not approve the $18 it would cost to print a run of books. So I had to get creative again.

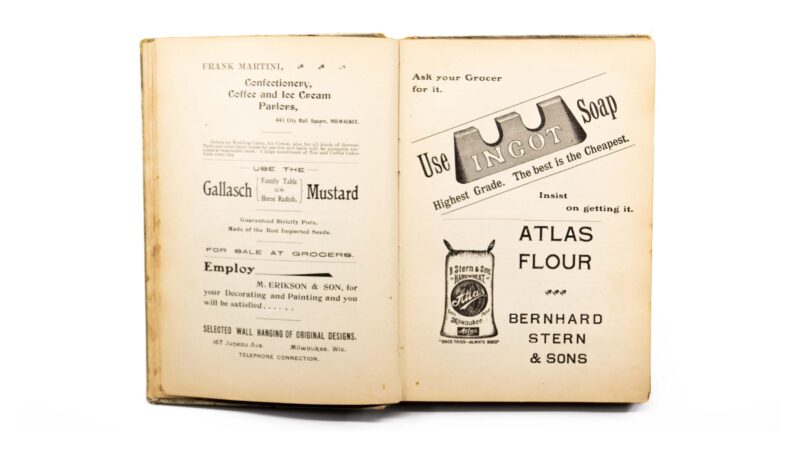

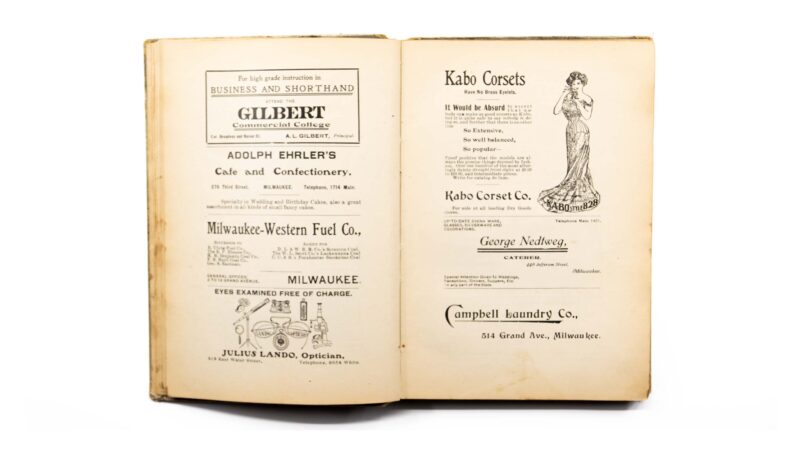

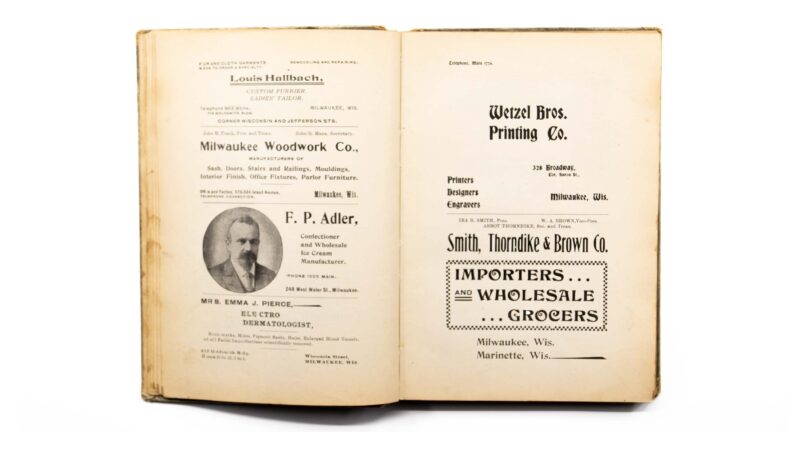

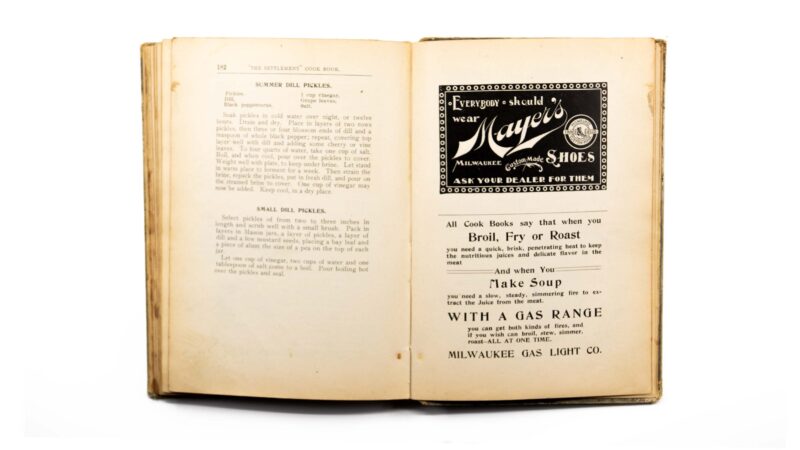

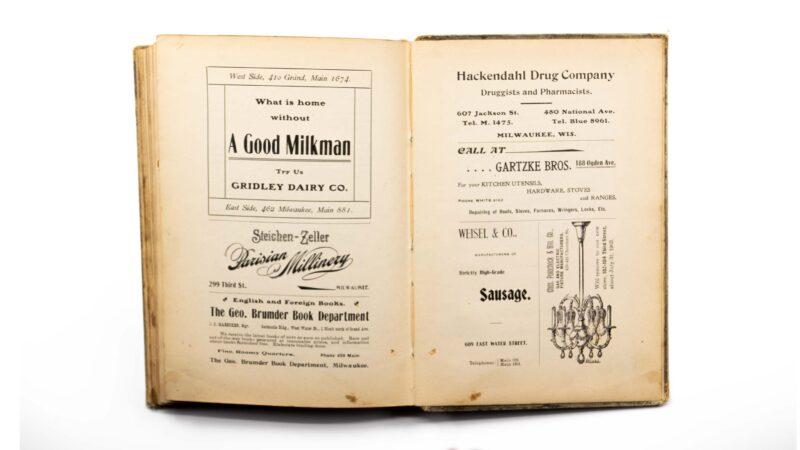

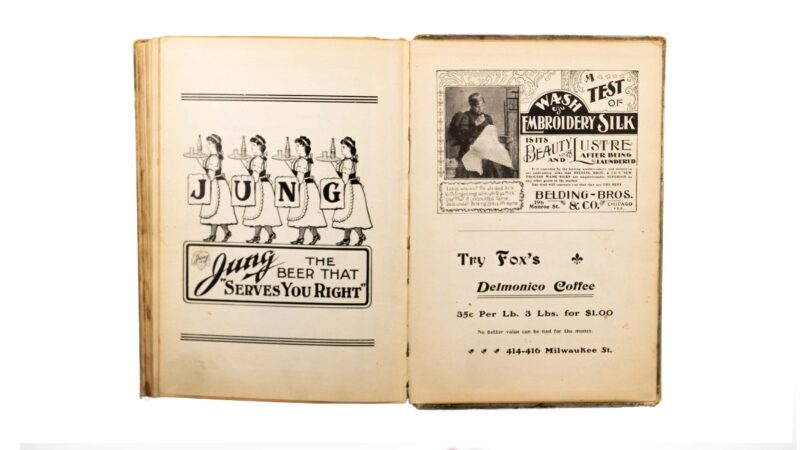

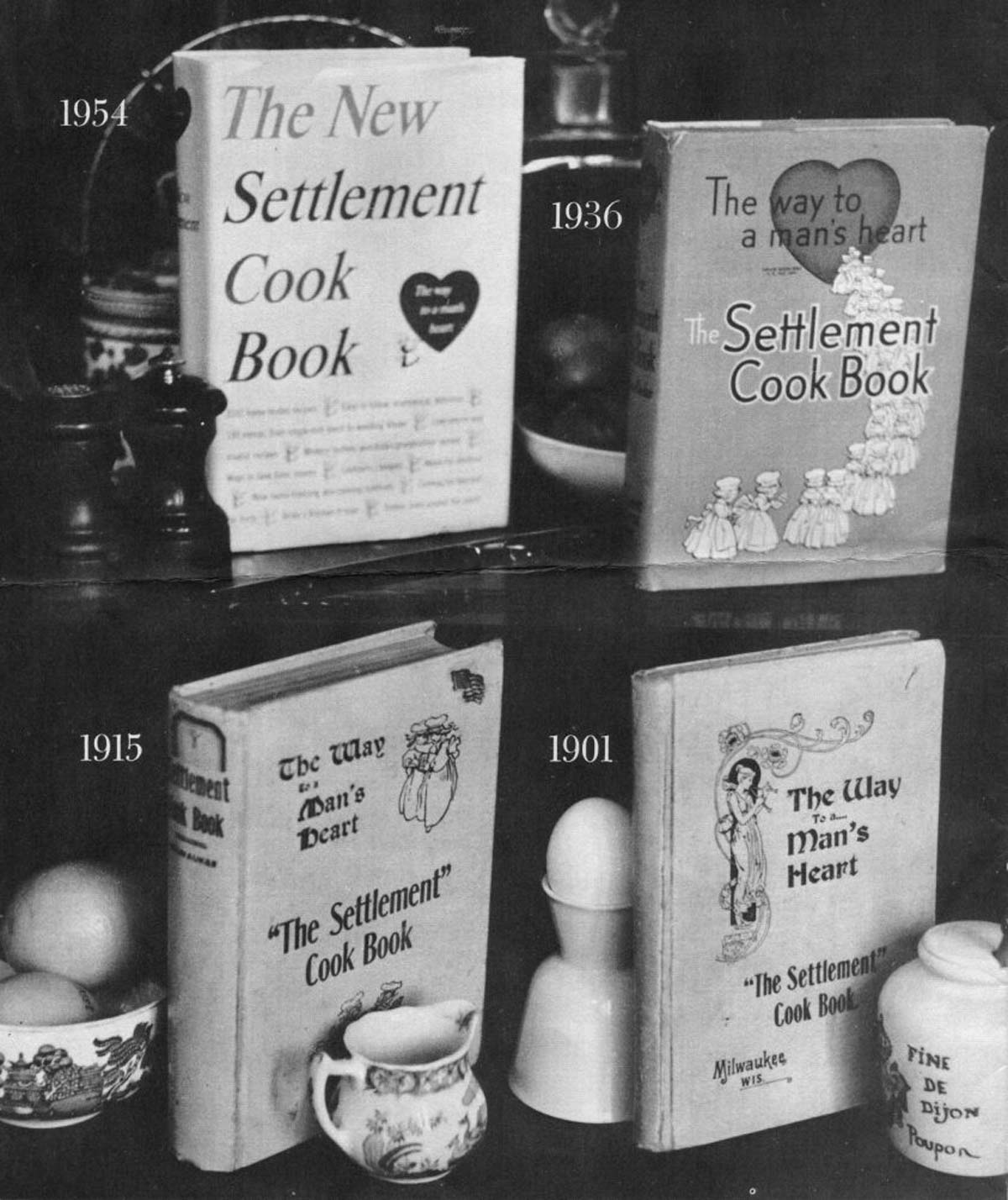

I went to local businesses whose goods and services might appeal to the women I expected to read the book to see if they would sponsor it through advertisements in the opening pages. Many were keen to the idea and paid to have their names in the book and so we were able to publish the first 1000 copies, complete with ads for baking soda, for clothing stores, and grocers, in 1901. By the end of the year the books were sold out; so we published 1500 copies of a second edition in 1902. Again they sold out.

The book really caught on. It allowed the Settlement House to grow and to change. In 1911 we moved buildings to the Abraham Lincoln house and expanded our operations. I kept editing the book every time a new publication was needed. I wanted to ensure that what we were promoting in the book continued to update with the changing situation in America and with the demographics that were drawn to the cookbook. On the one hand, it became more specifically Jewish because Jewish Americans loved all the recipes. On the other, I didn’t pay much attention to Jewish dietary laws, or kashrut, so it was still a good cookbook for anyone.

Throughout my whole time at the helm of the Settlement House, the cookbook was the foundational funding enterprise. We could keep most of our costs within the parameters of what we made from sales. And, as we grew, more people in the community began to understand our purpose and our importance; which only helped us gain friends and acclaim.

Eventually, the Settlement House became the Abraham Lincoln House and then the Jewish Community Center. It remains a vital space of community, connection, support and joy for people in the Milwaukee area.

And it all started with a book, some women, and the willingness to give it a try.