Jay Larkey

My wives really deserve all the credit. They were brave at times when I was scared. They pushed me to do things I didn’t even know I wanted to do. They showed me how to be a contributor to my community, in my own way.

It really started with Hinda, my first wife. She was an incredible woman who worked very hard to make the world a better place. She was the daughter of New York socialists who were always at the forefront of progressive change in their hometown, so fighting for what she believed in seemed to come naturally to her. It wasn’t quite the same for me.

She and I started getting involved in the fight for civil rights after we investigated the bussing system that had been implemented in Milwaukee following Brown v. Board. We decided to follow a school bus of black children to an all-white school to see how the integration policies were being implemented. What we saw there was shocking. When the black children arrived, they were marched in with all of their white schoolmates who’d already arrived staring and jeering at them. They were being treated like zoo animals by their own peers.

But then we realized that they weren’t really being brought together as peers. The school was segregated internally–white students and black students were not going to class together, so they weren’t getting to know one another. And at the end of the day, we witnessed the same thing: black students paraded out like a spectacle to be mocked and taunted by their white counterparts.

My wife couldn’t take it. She thought the whole system was inhumane and simply contributing to the problem that Brown v. Board was supposedly addressing. One day she even chained herself to a bus so that students from the segregated neighborhoods wouldn’t be bussed out, toward the waiting hatred of white children, teachers, and administrators. Instead of bussing, what she and others thought would work was creating more integrated spaces right in the center of the city. She taught at what was called a Freedom School alongside people like Lloyd Barbee who ran a civil rights organization here called the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC).

It was through our affiliation with MUSIC that we also got involved in other things like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Milwaukee Citizens for Equal Opportunity (MCEO). These three organizations were dedicated to integration of both schools and neighborhoods. And, as our experience with the bussing system suggested, one without the other was not a great recipe.

We turned much of our attention to housing, as did the whole country, in the mid- and late 1960s. It was a strange time of great anxiety and fear; but it was also a moment of possibility and movement. The Vietnam War was brewing and the fight for civil rights was being amplified by the voices of national leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. In Milwaukee, it was Lloyd, Prentice McKinney, Vel Phillips, and Jim Groppi who were leading much of the charge. Prentice was on the Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who called themselves commandoes. With the organizing power of Jim and Prentice working out of the parish at St. Boniface Church, CORE and other organizations initiated an equal housing march in 1967.

The marches were incredible and incredibly scary. When marchers crossed the 16th St. Viaduct into the all-white south side, they were met by angry mobs who cursed them, spat on them, and threw bricks and other vile things at their heads. The police didn’t protect the protesters; they simply set off some tear gas in an attempt to scatter everyone. It worked, but everyone was panicked and bleary-eyed and some were genuinely hurt.

Unlike my wife, I didn’t feel comfortable on the front lines; but I knew that I could help people who were brave enough to march on the front lines. So, I set up an emergency room in the basement of St. Boniface Church. I was a gynecologist by trade, but I knew that my medical skill set would help and I recruited some of my other doctor friends to come with me to the Church and be part of the team that would await wounded and injured demonstrators. We used all of our personal equipment and went around to various pharmacies to get supplies that we knew would come in handy for this particular situation.

I would like to think that I helped, but I know that the movement only moved forward through the sacrifice of those amazing young men and women who were out on 16th street every night for 200 nights.

While I was volunteering for the movement, I came to realize how poorly the black community was being served by the medical system. People in the ‘inner core’ as it was called at the time, didn’t have a good place to go and often had to travel a great distance to get any kind of medical care. And that which they received was underwhelming and often misguided. I saw that nutrition was a problem as was basic prenatal and post-natal care, which was my specialty.

It shocked me a little because I had already been the Chief Operations Officer and Medical Director of Planned Parenthood. I thought I had a good understanding of what was available to pregnant women in Milwaukee; but the black community was in a different and much more dire category. It encouraged me to advance their mission as much as possible and gave me even more impetus to increase the number of black doctors on staff with me at Sinai Hospital.

As the Chairman of the OB department in the mid-60’s I had already hired a number of black doctors and nurses. Some of my colleagues and the hospital administrators thought that this would mean white patients would flee; but they didn’t. A good doctor is a good doctor. And it encouraged more black women to seek out our hospital for care which I knew would be better than what they were getting elsewhere.

My wife also spurred me to work with what was called the Underground Switchboard, a really forward-thinking group of people offering help to those with mental health conditions and drug addictions. Often the folks receiving services were homeless or incredibly poor, and the Underground Switchboard helped point them in the direction of services that would help them stabilize their life and get the help they needed. It was a remarkable project and it really paired well with so much of what I was doing at Planned Parenthood or what we’d done with the Housing Marches.

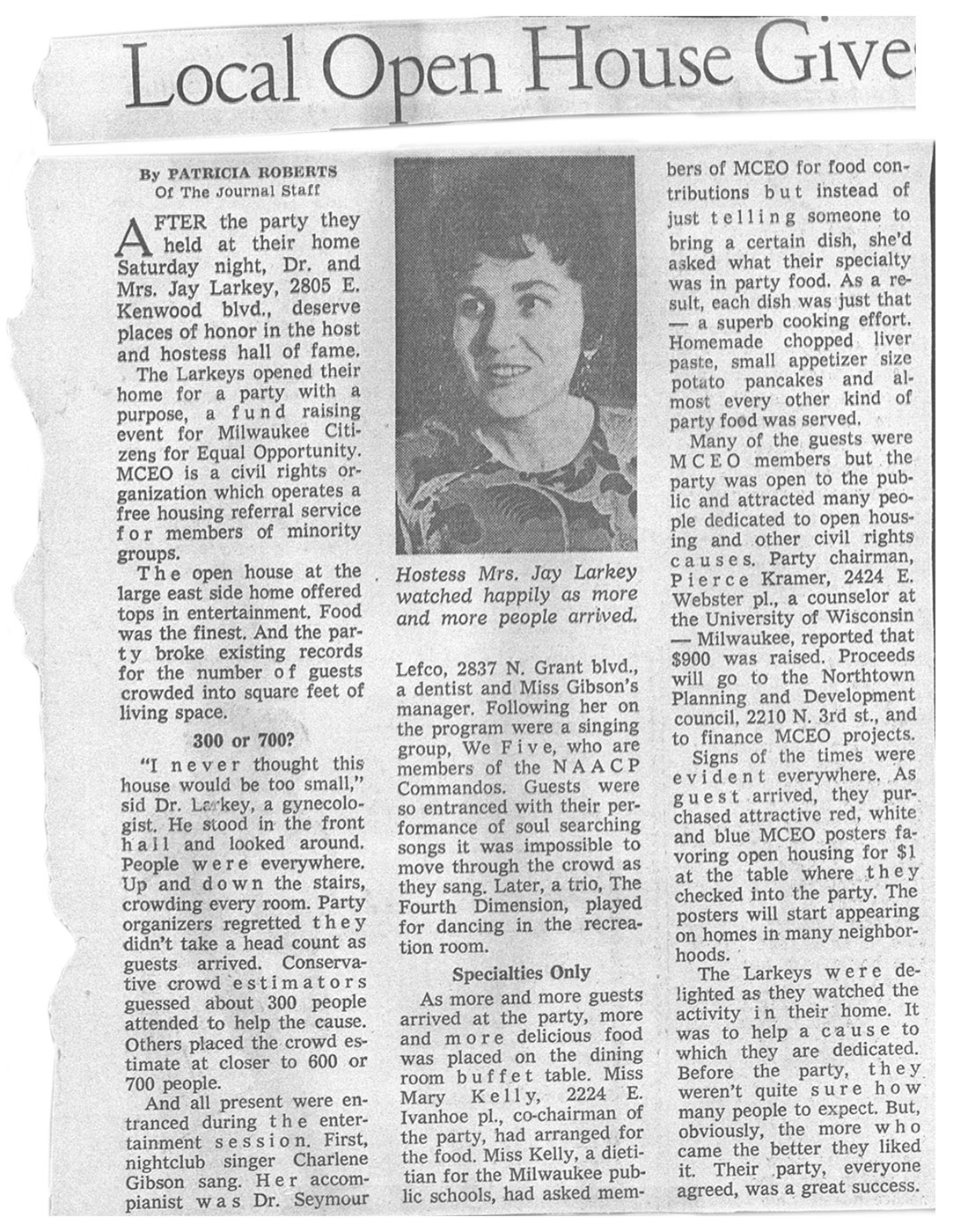

It might all sound very serious, and certainly the efforts we made were incredibly important. But we also had a good time. One night, near the end of the 200 days of marching, Hinda and I decided to host a Freedom-In Fundraiser at our house. The idea was that we’d have a fun-filled cabaret-style event to raise money for MCEO. We both thought our home would be big enough–we had a nice place on the East side and had hosted good parties before. But the turnout was incredible! Some people estimated that 300 people were there at one time! Hinda and I were overwhelmed. We raised a bit of money and everyone had a good time.

A month later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed. The Commandoes had just stopped their days of consecutive marching, but you can bet that we were all back out on the streets in a hurry.

In 1972 I was awarded a B’nai Brith Human Rights Award, but I always felt that my wife deserved it more than me. She motivated me to do almost everything that I was recognized for. What I sought to expose was the equality of each human being. I just wanted to make sure that I treated each human being like they were my brother. To me, this is partly what it means to be Jewish.